Leaderboard

Popular Content

Showing content with the highest reputation on 03/14/2023 in all areas

-

8 points

-

7 points

-

6 points

-

6 points

-

5 points

-

5 points

-

5 points

-

Julia tells her husband, "James, that young couple that just moved in next door seem such a loving twosome. Every morning, when he leaves the house, he kisses her goodbye, and every evening when he comes homes, he brings her a dozen roses. Now, why can't you do that?" "Gosh," James says, "why I hardly know the girl."5 points

-

4 points

-

4 points

-

3 points

-

3 points

-

3 points

-

3 points

-

3 points

-

TUNING FORK Chief of Police Will Keller poured the coffeemaker's water reservoir full. He thrust a coffee filter into the basket, added one scoop of freshly ground coffee -- ever since he'd ground his first batch, he'd never gone back to pre-ground -- added a healthy double shake of cinnamon, another coffee filter atop the first; he slid the basket into place, closed the lid, turned. He regarded his guest with calm eyes. "I can feel you vibratin' from here," he said quietly. "Have a set, darlin'." Marnie Keller gripped the back of the kitchen chair, staring down at her knuckles with a distant expression: she lifted the chair just a little so its travel would be silent, she set the chair's back legs down carefully, seated herself, stared at the sugarbowl in the middle of her Uncle's tidy tablecloth. "You were right," she said quietly. "Yeah, I hate that when it happens," Will said, looking at the cupboard as if coming to a decision: he went to the refrigerator instead, pulled open the bronze-toned door, withdrew three-quarters of a pie. He set the pie on the counter, managed to work two plates out of the stack, set them beside the pie; two swipes with an ancient, age-browned, sway-belly butcher: he slid the wide blade under a quarter of a pie, coaxed it onto a plate, did it again, placed the blueberry-smeared knife in the mostly empty pie tin and returned to the refrigerator. Marnie looked up at the sputtering hiss of whipped cream being dispensed thickly on each slice of blueberry pie; she watched dully as Will pulled open the drawer, brought out two forks, turned. Marnie leaned back a little as the white-crowned plate was set before her, fork to the left as she preferred: another moment and fresh brewed coffee, scalding hot and smellin' good, settled in beside the plate. Will set the plastic milk jug beside the sugarbowl. "Careful you don't chip that genuine heirloom antique milk pitcher," he deadpanned. Marnie looked up at him, unsmiling: she twisted the cap off the milk jug, carefully trickled a cooling stream into her coffee, returned the jug to its former position, handle toward her Uncle's chair. Will drug his chair out, legs chattering noisily on the spotless floor -- like most men, he didn't pretend to stealth under his own roof -- he sat, laid his forearms on the tablecloth, lowered his head and looked at his niece through shaggy eyebrows. "Report," he said quietly. "You were right, Uncle Will," Marnie said, her voice tight. "I generally am." "That's because you know what you're talkin' about." Will grunted, his eyes turning toward the living room. Marnie knew he was looking at a framed portrait, a shot of a young man with pale eyes: his son, the one he buried: his son, the one that was killed while working undercover. Marnie knew he was thinking how much he'd like to have heard those words from his own son, but that never happened; had he lived, had Will's son seasoned out some more, he might've told his father that yes, Pa, you were right -- but that didn't happen, and Marnie knew her Uncle Will would give a good percentage of his eternal soul if he could hear his son's voice frame those words. Marnie picked up her fork, almost caressed the creamy swirl of whipped cream with shining, stainless-steel tines. "Uncle Will," she said slowly, "I testified today." "You spoke well." "I demonstrated how I took them down." "Do you remember how you did it?" "No." Marnie placed her fork back on the plate, her pie untasted. "No, Uncle Will. I still don't. I've watched the videos and I watched video of my testimony, how I threw Paul Barrents like he was a rag doll, how I drove his rubber knife into his redbelly padded suit, but" -- her voice lowered to a hoarse whisper -- "I don't remember doing it!" Will nodded. "That's not unusual, darlin'," he said quietly. Marnie nodded, twisted her fork delicately in the whipped cream, more to have something to busy her fingers than anything else. "It was ... unusual ... for you to testify as to your actions ... by performing the actions." Marnie thrust her fork slowly, s-l-o-w-l-y through the whipped cream, through the top crust, then through the bottom crust. "I figured if my mind couldn't remember," she said slowly, "the rest of me could." Will nodded. "I've seen the same videos you saw, darlin'. I saw him pull the knife and come at you, that much was clear as a bell." Marnie's fork froze. For the first time in his memory, Chief of Police Will Keller, uncle to this pale eyed, very junior Deputy Sheriff, saw something in her eyes he'd hoped he'd never, ever witness. Marnie had that same thousand yard stare he'd seen in too many eyes, eyes that had seen too much. He knew his niece had known utter brutality when she was but a wee child, that she'd seen things before she was old enough for Kindergarten ... utter and absolute horrors that would curl the hair on a bald man's head. Will remembered the quiet discussions they'd held, sitting on the back steps, how Marnie worked through the puzzles of her psyche -- how she'd told her Uncle of her research, how she'd found most nurses were brutalized as young teens, and according to the head shrinkers, became nurses to help others heal, because they knew what it was to be hurt. She spoke of her pale eyed Gammaw, Will's twin sister Willamina, a woman who'd been brutalized in just such a way, a young woman who became both a nurse, and a deputy Marshal, then Sheriff, a Marine -- she said her Gammaw admitted she went into the Marines because she had enough rage and enough desire to kill to know she needed Marine Corps discipline to contain that Rage. "Not all girls that were hurt, become nurses," Marnie had said softly, as they sat shoulder to shoulder and hip to hip on his back steps, staring out into the nighttime shadows: "Gammaw became Sheriff so she could make things right." "Is that why you went into the Academy, became a Deputy?" He felt Marnie take in a long breath, sigh it out, felt her nod, her pigtails whispering on Carhartt canvas. "Yeah. I wanna make things right, Uncle Will." She turned her head, smiled ever so slightly. "I can't save the world. Don't get me wrong. I can't stop it all, but I can do some good." Now that same girl, that same young woman, sat across his round kitchen table from him, poking at her blueberry pie, remembering what it was to testify, remembering what it was to step into a man with a knife, remembering what it was to turn her badger loose on three at once. "I've kept myself safe, Uncle Will," she said, laying her fork down again: she picked up her coffee, carefully, using both hands, took a tentative sip, grunted. "Oh, that's good!" "Glad you like it. Cinnamon won't dissolve so I brew it in with the grounds." Marnie took another sip, set her mug down. "I've taken men down, Uncle Will. I've proven myself someone you don't want to trouble, long before I put on this uniform." She looked very directly across the table. "But you were right. When you're the new badge packer, you're going to be tried." She snorted. "Tried! Good God, three coming at me at a traffic stop and one pulls a knife!" "Which you put into his own belly, which you broke his wrist, which you dislocated a second one's jaw with a kick and you hammerfisted the third one's collarbone before he could pull a gun." Marnie nodded, blinked. "I'm not a violent person, Uncle Will." "I know you're not. You're sweet and you're patient and I know a doctor's son who has you so far up on a pedestal it's a wonder you don't have nosebleed." "You haven't touched your pie, Uncle Will." "Neither have you." Marnie looked at her fork, looked at her Uncle, looked down at her hands, pressed flat on the tablecloth. She closed her eyes. "How badly will I be shaking when I lift my hands?" "You were steady enough with your coffee. Now tell me about testifying." "All those practice runs helped." "My Baby Sis always did like simulations. She thought you always did really well in the witness stand in the simulated criminal cases." "It paid off today." Marnie snorted, stabbed her pie viciously, looked up. "I was reading about Old Pale Eyes. I read where court was entertainment in those days. It was always well attended, and the attorneys were showmen with fine language." "Some things never change," Will muttered. "Attorneys, anyway." Marnie forked up her first bite of pie, frowned at it as if it were a rare specimen, worthy of scrutiny. "Today, as we left the courthouse, I heard someone say they'd never seen such entertainment on stage, and if I was testifying in court again, they'd be sure to attend!" She thrust pie and whipped cream between her lips, chewed: Will nodded, stabbed into his own, steel tines making a bright noise as they penetrated to the porcelain. "Were you nervous, Marnie?" Will asked quietly. "No, Uncle Will," Marnie admitted. "I was dead calm. I came down out of the witness stand and said 'I can show you what I did, better than explain what I did,' and my three assistants in well-padded suits came to the center deck, and the fight was on!" "How do you feel now?" "When I came in here, I was wound up like an eight day clock." "I could feel you vibratin' clear across the room. How about now?" Marnie shrugged. "I'm not much of a tuning fork." "I knew it." "What's that?" Marnie took another bite of pie, looking at her Uncle with bright and innocent eyes. Will grinned, took a noisy slurp of coffee. "Blueberry pie and whipped cream is good for what ails ye!"3 points

-

3 points

-

Had some German relatives visit and took them to Grand Canyon. They strolled directly to the edge and looked down. Their comment was "Wonderful! In Germany there would be a fence!"3 points

-

3 points

-

3 points

-

2 points

-

2 points

-

OLD SOFTY Sheriff Linn Keller's right shoulder dropped. The troublemaker was fast, he came up to guard against a right-handed punch. He wasn't expecting the work-hardened left hand that seized a good handful of his collar, he didn't expect to be shaken back and forth, just before he was yanked hard forward and hard back: the back of his head bounced off the Spring Inn's heavy door. His vision hazed and sparkled and he wondered why the ceiling was suddenly so much closer. Beside the Sheriff, the Navajo chief deputy, with an abbreviated twelve-gauge, regarded the slowly retreating semicircle of former challengers to the Sheriff's authority. Paul Barrents' eyes were black, polished, expressionless: he'd come in behind the Sheriff, he'd closed the door quietly, he'd taken his position, established his stance: obsidian eyes were the only things that moved, and every man there felt that hard, uncompromising look, that unmistakable feeling that Barrents was establishing the sequence of men he'd kill: who first, who next -- and with a twelve-bore inside a concrete block beer joint, nobody there doubted the deadly consequence of that silent, watchful deputy's actions, should he let slip the leash on his blued-steel war-badger. Sheriff Linn Keller seized another man's wrist, pulled: his fist drove up, hard, blasting through shirtfront and muscle wall, driving the diaphragm up into the lungs, punching every bit of the man's wind out of shocked lungs: when the Sheriff uncorked his punch, the other fellow's feet came off the ground: those watching, staring, mouths open, those on this public street, beholding sudden violence, realized their pale eyed Sheriff was both faster and much stronger than they'd realized. Sheriff Linn Keller sat at his desk at home, hunched over the blotter, frowning a little as he wrote. He did this, when he'd had one of those days: sometimes he'd throw himself into cleaning the barn, sometimes he'd whistle his stallion over and spend a great deal of time currying him down, fussing over hooves and fetlocks and brushing out mane and tail, his hands busy, his eyes hard: the stallion stood for these ministrations -- usually the spirited mount would be dancing impatiently, sometimes he'd nip at Linn's backside, sometimes he'd dance just out of reach, snorting and shaking his head. When Linn was troubled, though, the stallion would come up to him, snuff at his middle, then lay his big head over Linn's shoulder: Marnie had watched, silent, as her big strong Daddy would caress the Appaloosa's neck, she'd pretend not to watch as her Daddy buried his face in a stallion's mane and grit his teeth as his face reddened and scalding tears ran down his face. She'd watched her Daddy work seventeen year old summer help into the ground, she'd watched him reduce sinners to a peaceable status through less than gentle means, she'd laid on her belly at the edge of a sinkhole, reaching in and grabbing a desperately extended wrist, her Daddy on his belly on the other side of the same hole: she'd pulled, with him, she'd fought to her knees, with him, then she'd stood, an adventurous boy hanging from their grip, wet, muddy, scared and glad as hell to be out of a hole that seemed intent on swallowing him, and Marnie looked across at the look of utter triumph on her Daddy's face. Marnie watched as her Daddy's steel nib dip quill scratched on good rag paper. He was frowning, concentrating: a quick dip in the black India ink, a wipe on the glass mouth of the ink-bottle: Marnie knew he was mercilessly marshaling his words, arranging them in neat ranks, disciplining the inner man with the expression of the outer man. Linn left the single sheet on his desk blotter: Marnie knew the ink he used took a little to dry; he did not sprinkle it with blotting-sand, he did not press blotting-paper and rocker it firmly down: she knew the rag paper would not suck up the ink like the cheaper wood pulp paper did, and when he left his script to dry, she knew he meant for his words to be distinct, black, legible forever. Marnie waited for her Daddy to go to bed: his silent, sock-foot tread up the broad stairs was slow, the walk of a tired man, but his shoulders were back, squared, his back straight: from this, she knew, he was satisfied with his day's work. Marnie waited, silent in the shadows: she had the patience of a hunter, and she waited until she knew she'd not be seen, before slipping like a ghost through the nighttime shadows. She had a small light, cupped in one fist: she allowed a cautious crack in her enveloping grip, diffused light fell to the single sheet. Marnie read, and as she did, she nodded, blinking, and as she read, she bit her bottom lip. This night have I heard true beauty. I stood in snow-shadowed dark As shattered clouds drifted earthward round about. Nearby, in the snowy wood, The Wild sang their ancient song. Still and stricken did I stand, Music-ensorcelled, snowy man: Heard the Trickster, Coyote, Sing in many-throated, Untamed, Harmony. Cold alone broke enchantment's spell, Yet is its song laid 'pon mine soul Like a blanket of sunrise given me On the first day of Creation! Marnie re-read her Daddy's words, then shut off the little light hidden in her fist. She felt a shadow move, turned; her Daddy was standing at the bottom of the stairs, silent, unmoving, watching her. Marnie Keller -- Sheriff's deputy, proven warrior -- ran like a little girl across the nighttime floor, seized her Daddy, held him with a desperate strength, shivering: she held him tight, tight, as his big, strong, Daddy-arms wrapped around her, held her the way a big strong Daddy will hold his little girl. Next day, as Jacob handed him the weekly newspaper, Sheriff Linn Keller settled into his desk chair, looked over his hand-written list of calls he had to make, then looked at the sheet he'd written the night before. In morning's light he didn't think that much of what he'd written, but he took a second look at the sheet. Later that day he took it into town, carefully protected in a brown manila envelope and this, in a file folder: when he brought that single hand written sheet home, two days after, it was behind glass, in a frame, and he hung it near his desk, where he could see it. He wasn't all that impressed by his own words. No artist is ever satisfied with his own work; every author thinks his words are uninteresting drivel; every master carpenter will frown at his finished product and pick out every last flaw and shortcoming in the work of his hands. No, what inspired this pale eyed lawman to frame the work he'd written after a difficult day, was not the black ink marching in regular lines across rag paper. It was a single wrinkled spot, where a young woman read those words, and her heart overflowed her eyes, and one spot of her appreciation dropped, wet and circular, onto the paper. That framed work hung near Linn's desk for the rest of the pale eyed lawman's life, and for several years afterward. Every time Linn looked at that framed sheet, he smiled a little, every time. Every time he looked at it and smiled, he remembered a daughter's whispered words as she rubbed maidenly tears into his shirt front, scrubbing her face against the reassurance of warm Daddy-flannel: "Oh, Daddy," she'd whispered, then sniffed, hiccupped, looked up at him, her face wet, her pale eyes bright, the expression of an adoring little girl: "Oh, Daddy," she'd whispered, "you're just an old softy!" Linn Keller, who'd seized a barfight bully by the shirt and pressed him, one-armed, up to the low ceiling -- Linn Keller, who'd seized and disarmed large and angry people bearing a variety of weapons -- Linn Keller, who knew what it was to make that final, tenth-of-a-second decision, whether to put that last tenth-of-an-ounce on this trigger, yes or no -- Linn Keller, who in his time had been shot, stabbed, cut, run into, run over, whose corroded soul a street evangelist tried to save -- Linn held his little girl in the nighttime silence of the ancient ranch house, held her tight, felt her shiver a little: Marnie felt her Daddy's silent laughter, felt him bend a little and kiss the top of her head and heard his whisper. "I reckon so, Princess."2 points

-

2 points

-

2 points

-

You might outrun my old Chevrolet But you can't outrun my old two-way I wear a hat just like a Mountie I'm the sheriff of Boone County And you're in a heap of trouble boy Old, old song2 points

-

2 points

-

2 points

-

2 points

-

2 points

-

2 points

-

1 point

-

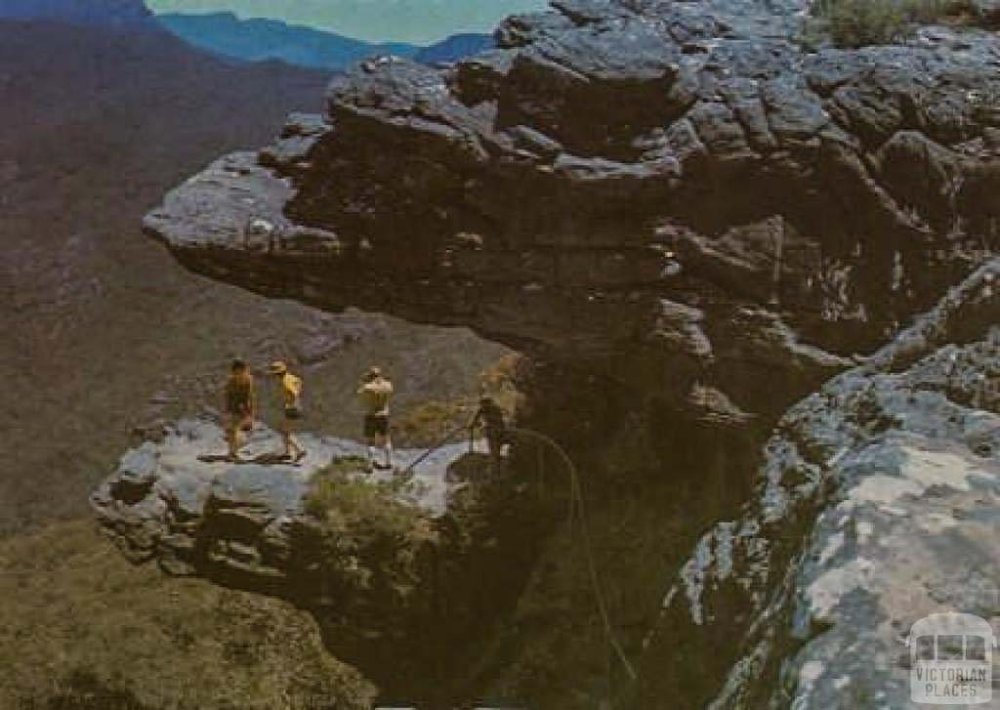

Still there. The PC crowd renamed it 'The Balconies" They have a fence to keep you from walking out onto it but it apparently doesn't stop people from climbing over it and venturing out onto the ledge. The Balconies a.k.a The Jaws of Death – The Grampians, Victoria, Australia1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

Why does seem like it ought to be called "Tours by ACME, Wile E. Coyote, Guide"1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

as to the liver , ya can keep it all to yourself only use for it is fish bait CB1 point

-

..... and don't forget the fact that the picture itself probably wants you dead too ....1 point

-

1 point

-

Some German folk live in that-ish area and have made it the wine capital OF THE WHOLE WORLD !! As for mosquito repellant, they've had to upgrade to 12 gauge ......1 point

.thumb.jpg.42f9340f5815e3915f9a0b0991f5aa8f.jpg)

_02-781336.thumb.jpg.f4a75bbb74124e28370c8d589db5938f.jpg)