Leaderboard

Popular Content

Showing content with the highest reputation on 03/13/2024 in all areas

-

8 points

-

8 points

-

7 points

-

7 points

-

6 points

-

6 points

-

6 points

-

6 points

-

6 points

-

Ours were very similar, only with ornate cast iron scrollwork, screwed down to the wooden floor, and ours were singles instead of a side by side. Inkwell, yep ... but our desktops were nowhere this nice. Ours had initials, names, gouges ...6 points

-

5 points

-

5 points

-

5 points

-

5 points

-

BELLIED DOWN Victoria Keller was a very proper little girl. She wore frilly dresses and shiny slippers and her Mama fussed over her hair and delighted that she had a pretty little girl she could raise as a girl. Victoria was obedient and Victoria was gentle, and Victoria had pale eyes and Victoria watched and listened. Sometimes Victoria decided she'd had enough of being a girly little girl. Michael, of course, was as close to his sister as any twin, but Michael was most definitely all boy: Michael was his Pa's shadow, Michael loved getting into "Stuff" with dear old Dad, and Michael delighted in getting away with anything he could ... never anything terribly bad, but like generations of his predecessors, he had an adventurous spirit and a curious nature. Michael and Victoria learned to read, each one determined to out-do the other, yet each equally determined to bring the other up to their level: what one learned, the other learned, and quickly, and so it was that two pale eyed children of that long tall Sheriff disappeared as they sometimes did, leaving behind nothing more than the fading sound of hoofbeats. The solid built barn beside the Firelands Museum still stood, still sound, still protected by a granite wall on one side, in a natural lee: winter's snows never piled terribly deep, it was easily accessed to clean out second hand horse feed, or to haul in hay, and two spotted Appaloosas walked between the barn and the museum -- a stone museum that used to be a house, the home of one Sarah Lynne Llewellyn, until she took her maiden name back after becoming a widow. The pair rode up the narrow passage, through a hidden opening, into the high meadow above, dismounted: they climbed with the fearlessness of children, they delighted in looking out over an incredible distance, visible from this high up, and they took turns looking down the sheer drop, giggling as they dizzied themselves, then leaning back against the sun-warmed granite, looking up at the incredibly blue sky overhead and dizzying again. They navigated the narrow, ancient path with the ease of the fearless young, came out on the shelf known to their ancestors as a place of refuge, a place of contemplation. "Did you bring it?" Victoria asked quietly. Michael nodded. "Bring yours?" Youthful hands thrust into pockets, brought out small, high-intensity flashlights. "It might be a den," Victoria cautioned. "It has been, you know." "I know. I'll take a look first." Two children moved to the low opening, knelt, then bellied down: they squirted beams of incredible brightness into the dark. "I don't see much." "I don't see any eyes." Michael slithered in, fitting easily -- he thought he would, an ancestral Jacob made it in, and back out, when he interred his ancestral Bear Killer here. "Michael?" "Huh?" "To your right. What's that?" Michael swung his light, blinked. There was not enough room to come up on hands and knees; he slithered forward without difficulty. "Ummm," he said, wiping at something on what looked like a square tin box. "Victoria ... you ever been here?" "No." "This has your name on it." "What is it?" Michael gripped the square tin, or tried to: he frowned, tried gripping his light in his teeth. "Shoot your light over here. I gotta use both hands." Michael shut off his light, thrust it into a pocket: he gripped the tin with both hands, worked it back and forth, dragged it toward him. Another, behind it: he stopped, shifted so Victoria's light could sear past him, illuminate the plate on the second square box. He rubbed the plate across the front. "Victoria?" "Yeah?" "This one has my name on it." "Are there any others?" Michael pulled his light out, clicked it on, swung it around. "No." He turned his light off, thrust it away: he worked backwards, dragging one box, then the other. They backed out, emerging into daylight: Victoria got up, squatted impatiently as Michael wiggled backwards out from under the gap in the mountain, dragging one heavy tin box, then the other. “Ow.” “Ow?” Victoria bellied down again, squinting into the darkness, then wiggled to the side as Michael’s boot soles advanced toward her. It was more spacious inside than at the opening: Michael’s quiet-voiced “Ow” was because he’d banged his gourd on the narrowing opening as he slithered out backwards. Victoria stood, swatted at her front, frowning at how filthy she'd gotten: Michael stood, did the same. Two pale eyed children studied the tin boxes, gripped the handles on top: they were easier to pick up, now that they were standing – the boxes were heavy, awkward; they managed to duck walk down the narrow path, leaned back a little, hugging the boxes to their bellies, their shoulders rubbing the granite as they did, the edge of their tin box hooked on their belt buckle. It helped, a little. They got down to their horses, stopped and washed their hands in the near-freezing stream: Michael slung his hands off, frowned at his front -- typical boy, he almost wiped his hands down his belly and thighs -- he stopped, reached back, dried his hands on the seat of his blue jeans. Victoria tilted her head, considered this, then did the same thing. Two riders walked their Appaloosas down the hidden path, came out between the still-solid old barn and its drowsing ghosts, and the museum, watching them with glassy, unblinking eyes: they made it home, they donated what they'd been wearing to the friendly local Maytag and got it thrashing, then scampered upstairs in underwear and socks. They were showered and into clean clothes, their wet duds anonymous on the populated clothesline behind the house, before their Mama got home. That evening, Michael and Victoria presented themselves at their Papa's desk: they stood, shoulder to shoulder, each carrying a wiped-clean tin box that Linn thought appeared heavy, judging by the way they held them. Michael said "Sir, your advice?" Linn hadn't gotten to whatever it was he'd been thinking about. It was rare for his children, his youngest, to face him with such solemn expressions, even moreso for them to present with an obviously-heavy burden in hand. Michael flipped a folded towel onto his Pa's desk. "I don't want to scrape up your desk," he said, "this is kind of heavy." Linn reached over, put a hand under the box, raised a surprised eyebrow. "Yes it is," he murmured. Victoria was barely able to pack hers, using both hands: Linn gripped her box as she offered it. Linn saw her name was hand-chased on a plate, riveted to the front of the age-darkened metal. "They're locked," Michael said. Brother and sister watched a light dawn in their father's eyes. He looked at one box, then the other: he looked at his children, at the boxes: he rose, took two long strides to a shelf, ran his finger along the row of reprinted Journals. He pulled one down, flipped quickly through it: closed it with a snap, thrust it back, hooked the next with one finger, tilted it back, gripped it, brought it down. Michael's hand opened as Victoria's hand opened and turned: they held hands, silently sharing an uncertain anticipation as they watched their father's suddenly-serious eyes scan quickly, as he ran fingertips down the page, as an unguarded expression of discovery tightened the corners of his eyes, broadened into an actual smile. He snapped this Journal shut, carefully threaded it back into its place on the shelf: he turned, looked at his desk, looked beyond it to his Mama's ancient roll top desk. Linn nodded, looked at his two youngest. Michael felt Victoria's hand tighten in his. Linn went to his desk, pulled open one drawer, another: he pulled out a keyring, fingered through the jingling sawtoothed collection, separated one key out – instead of flat and toothed, it was old-fashioned-looking, dark and round-shafted, a hollow in its end, with a single, spade-shaped projection at its end. Linn went to a shelf, removed two books, two more, set them aside. He reached in -- Michael and Victoria saw his elbow move a little, but they could not see what was out of sight on that eye level shelf -- Linn did something, turned something, it looked to the twins as if he turned his arm a little and pushed something, then turned his hand again: he replaced the volumes, strode quickly to his Mama's antique, ancient, heirloom rolltop desk. Linn unlocked the ancient desk, carefully raised the curved, flexible wooden roll top, then brought it back down, silently counting the wood crossmembers as they passed a dimple, placed with a centerpunch by its appearance: he held the rolltop with one hand, inserted the key, turned it, opened a little hinged door: he removed the key, inserted it deep into the cubby the little hinged door revealed. Carefully, slowly, he withdrew his hand, and with it, a small drawer, with a lid. He withdrew the key from its front, inserted it straight down into the drawer's lid, turned the key. Michael and Victoria saw him remove the key, place the well populated keyring on the desk's writing surface. He lifted the lid on the drawer he'd just brought to light and withdrew a single key. Linn turned, walked over to the two metal boxes. His thumbnail explored a little tarnished-silver plate -- he found something -- a click, the plate slid aside, revealing a keyhole. Linn slid the just-retrieved key into the darkened metal box's keyhole, turned it, lifted the lid: he did the same for the second box. Michael was containing himself with an effort; Victoria was bouncing on her toes, grateful she was in sock feet, elsewise the hard little heels her Mama liked her to wear, would have beat a nervous tattoo on the hardwood floor. Linn sat down, looked at these, the youngest of his get. "Thank you for bringing these," he said. "You're welcome, sir," two young voices said in a soft-spoken chorus. "You got these from the High Lonesome." Two young voices again: "Yes, sir." “Good.” Linn looked at his two youngest. "I think ... it's time."5 points

-

4 points

-

4 points

-

SUDDEN GAIN "I have something for each of you." Linn rose, walked over to the gun case. He opened the door, brought out a pair of lever action rifles, brought them back. "You two have proven yourselves responsible and trustworthy." "Thank you, sir," two soft little voices replied. He handed one to Michael and one to Victoria. "Chamber check." Two young children jacked the levers open, looked into the action, looked back. "Clear," they said in one voice. "Close and half-cock." Actions closed, carefully, young thumbs laid over hammer spurs, pulled triggers; the hammers went to half cock. "You each hold a model of 1892 Winchester rifle. They are chambered in .357 Magnum. They were originally .25-20, but they were converted, and I'd like to kick the fellow who converted them." "Sir?" Michael asked: Victoria's question was spoken with her eyes and not her voice, as was usual with them both. "I know in practical terms the .357 is a better choice, but my father had a 92 in .25-20 and I loved that little rifle. He traded it off for a Remington Matchmaster and never liked it. I've been hunting for a .25-20 ever since. When I found these a few years ago, I had them engraved and gold inlaid, and I set them back for the right time." "A few years ago, sir?" Michael asked. Linn grinned, nodded. "The day you were both born." Two young heads nodded solemnly. "Ground the butts." Two rifle butts came down on the holder's right foot. "Look at the muzzle engraving." Young eyes regarded gold-inlaid vining encircling the muzzle, slithering with a barbaric splendor rearward for three fingers' width. "Now take a look at the breech." Michael took a step back, looked behind, then swung the rifle level, having satisfied nothing of importance, that no one, was behind him: he considered the matching, gold-inlaid vining around the breech end of the barrel, then the side of the receiver. In an ornate circle, an armored angel bearing a flaming sword: above, in a banner's arc, Michael: in the banner beneath, Angelus custos. "Victoria." Michael stepped forward, Angela stepped back: she frowned as she studied the barrel breech's vining, the receiver's gold inlaid, hand chased circle. Within, a mounted warrior in feminine armor, astride a rearing horse: in an armor-gloved fist, held triumphantly overhead, gripping a silver-headed lance: in the over-arching banner, Victoria; in the banner beneath, Soror Valkyria. "Now." Two solemn-eyed children grounded their rifles' butts on the arch of their right foot. Linn reached into one tin box, then the other. The cloth within was in surprisingly good shape: it appeared to be a light weight canvas, and appeared to be ... waxed, maybe? -- Linn held the edge of the nearest box with one hand, muscled the poke out with the other, set it on his desk. Solemn young eyes followed his efforts. He did the same for the second box. Each poke was tied with stout red cord. Linn worked the knot on each, a little, freed each sack's neck, drew them open, one, then the other. He looked in each sack and nodded. He reached in each one and brought out a tiny, individual cloth sleeve, handed one to Michael, the other to Victoria. "Take a look." Each child slid thumb-and-forefinger into their individual, flat little sleeve, withdrew a silver coin. "We'll have that inletted in your rifle stock," Linn said. "I know just the man for the job." Linn reached into the nearest poke, Michael's poke, and withdrew a gold double eagle, handed it to Michael: he picked one out of Victoria's poke, handed to her. "Take a good look," he said. "It's no wonder these were so heavy!" Michael and Victoria looked at their double eagles, looked at one another, looked at their Pa, handed them back. "This," Linn said, "represents a fortune. The way things are going, we will be wise to keep these as they are, in gold instead of Yankee greenbacks." "Sir, where did these come from?" "Do you remember Old Pale Eyes, way back when?" "Yes, sir." "He had the notion that he should provide for his children." "Yes, sir." "He had gold in a New York bank that wasn't found until after your Gammaw took office." "Yes, sir." "His son Jacob had the same idea." "Yes, sir?" "Jacob consulted a Gypsy trick rider named Daciana. She had a crystal ball and some said she was a witch-woman. I don't think she was a witch, really, but I do think she was a wise woman. “She told Jacob how he should provide for those to come." "Is that why mine says Michael and hers says Victoria?" Michael asked. "Yes it is." Michael frowned. "How do we keep all this safe, sir?" "What is the military principle of defense?" "Layered principle of defense," two young voices chorused. "What is the first layer of defense?" "Knowledge!" "Who do we tell about this?" The twins looked at one another, looked at their Daddy. “Nobody?” Linn winked, nodded approvingly. “Exactly that,” he affirmed. “Nobody. Why do we tell nobody?” “ ‘Cause the Baron von Ripemoff will break in an’ take it if we do!” Michael blurted. “I was gonna say that!” Victoria protested. “What else might they take if they broke in?” “Everything,” Michael said sadly. “Yep,” Linn nodded. “Everything not nailed down, wiring out of the walls, copper pipes, Christ off the cross and they’d come back for the nails!” Linn closed each box, turned the key in the lock. “I’ll arrange tomorrow,” he said, “to have those silvers inletted into your rifle stocks. I’ll give Marnie a call and see if she can help us out.” Delighted eyes looked at each other, looked at their Pa. “Marnie!” two young voices breathed in a quiet-voiced chorus. An attractive young mother sat down in front of her screen, her pink-cheeked, shining-eyed little boy on her lap, looking around, very obviously interested in the world around him. “Hi, Daddy,” Marnie smiled, then turned to the toothless, grinning little boy on her thigh: “John, say hello to your grandfather.” “Wa’l hello, John William,” Linn grinned. “You smokin’ cig-gars yet?” “He doesn’t have a grandfather nearby to teach him bad habits,” Marnie laughed. “I’ll have to remedy that!” Linn declared happily. “Say, you recall those two rifles I had you arrange to have engraved?” “I do,” Marnie replied happily. “Do you reckon you can arrange to have a silver dollar inletted into each rifle stock?” Marnie lowered her head, kissed her warm, wiggling little baby boy on top of his head. “Five minutes ago, or do you need it sooner?” Linn pushed back from his desk, looked to his right: Michael and Victoria moved in front of the screen, each holding their rifle like they considered their personal carbine as the most precious thing they’d ever handled. Marnie laughed quietly. “Daddy, how would you three like to make a road trip?”4 points

-

4 points

-

4 points

-

4 points

-

4 points

-

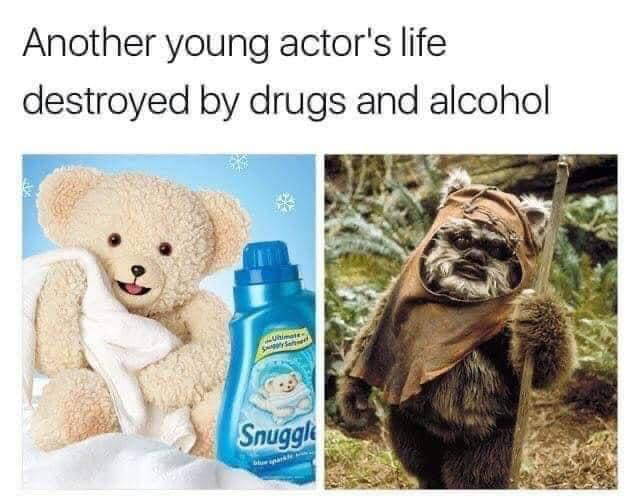

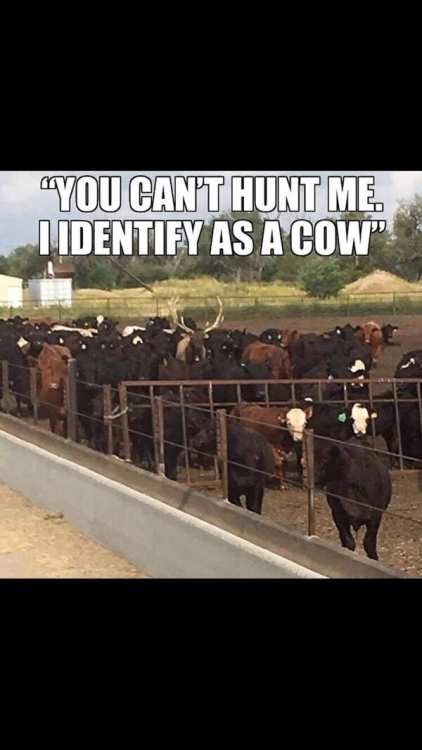

That almost killed my wife! I thought she was going to have a coronary she was laughing so much.3 points

-

I don't watch the Academy Awards, but I always check the see who won. It's a great way to get a list of crap I don't ever want to watch.3 points

-

3 points

-

3 points

-

It's odd...I really didn't like it as a kid, but now I don't mind it. Plus it's very useful in cooking.3 points

-

3 points

-

3 points

-

3 points

-

3 points

-

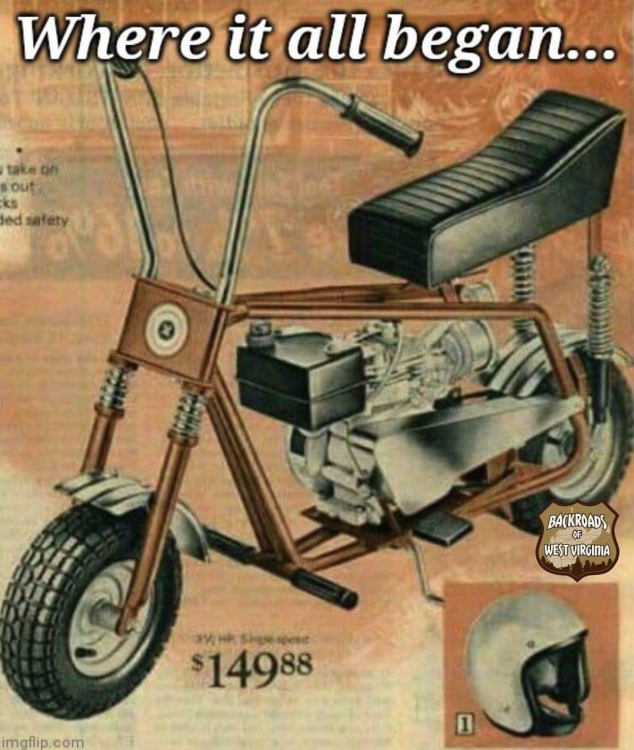

My laugh at the above post is because back in the 1980s I built one of those to use in the pits at big races to get around quickly between the several cars that I crew chiefed for. I used a ten hp Tecumseh engine and heavy duty centrifugal clutch built for go kart racing to power it. For fun, we put a drag slick on the back wheel, a kart header, a racing carb, and a disc brake on it. The guy that built the engine added a hotter cam and a higher compression piston, ported the block and installed a larger intake valve. We figured that that engine probably made twenty-five or more horsepower with the governor disabled. The mini bike might have weighed seventy pounds, (I could pick it up with one hand) and my boss/racing partner weighed a hundred and forty pounds soaking wet with a horseshoe in both back pockets! We used that thing for a couple of years around the drag strips, often to tow one or another of the cars through the staging lanes, but when we got the chance, ol’ Billy, my partner would make an 1/8 mile pass with that little monster. It did impressive burnouts and would run well over 70 mph!! I wish I had it now! We never knew how fast it would really go. Nobody ever had nerve enough to run it wide open through the quarter! I don’t know what ever happened to it. Three and four wheel ATVs got popular in the pits about that time and they were much safer for anyone to operate!!3 points

-

3 points

-

3 points

-

2 points

-

2 points

-

Don't put Carl don't just yet. Anyone who would dress and arm himself like that and then go into a crowd of fighters might be a damn fool......or he might just be the meanest SOB for miles around.2 points

-

Wouldn’t trade my time in the military for 10 Million dollars. Wouldn’t do it again for 100 Million.2 points

-

All of the homemade Bread Pudding I grew up eating did not have Raisins in it. Cinnamon yes, raisins no.2 points

-

I have no idea what recipe Mama used. According to the internet, bread pudding is stale bread mixed with milk or cream, and egg, then baked. So - baked French toast. While bread and butter pudding uses both raisins and spices. The recipes I've seen call for sultanas, which would be called golden raisins here in the states. Dried white grapes, instead of the dried red grapes that make normal raisins. But I remember Mama's having both raisins and cinnamon, so I guess she made a closer to bread and butter pudding.2 points

-

2 points

-

It's a heavily rust encrusted .32 kit gun he had turned up with a plough. The truck is the body of a 1940 Powerwagon that was in a ranchers field on top of a Datsun pickup frame and engine.2 points

-

Taken from a motorcycle. I used to work with the guy in the RatRod. See if you can see his hood ornament. https://m.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=pfbid02E6YpYQn2MhK6AvMnq7ohgbaHadGn1bnkQPjhagMSWqEUn5hJiEHqBmF2f3q8bSzzl&id=100000665976014&mibextid=Nif5oz2 points

-

2 points

-

2 points

-

So that's different from American bread pudding? Mama used to make bread pudding all the time. A cheap dessert using stale bread.2 points

-

2 points

-

2 points

-

For reasons stated elsewhere in the Saloon, I offer this one AGAIN today! We now return you to your regularly scheduled program!2 points

-

2 points