Leaderboard

Popular Content

Showing content with the highest reputation on 11/29/2023 in all areas

-

8 points

-

7 points

-

7 points

-

5 points

-

5 points

-

DID YE TALK T’ GOD ABOUT IT? Sheriff Linn Keller removed his Stetson as he addressed their hired girl. He apologized in a most gentlemanly manner for causing her more work, and asked if she could possibly tend his suit, for he’d managed to get it rather dirty: from anyone else, it would have been a demand, an order, but from the pale eyed Sheriff, it was couched as a request, and she’d discovered that when he parsed it as a request, it was just that. This was relieving to their hired girl, for tending the household was no light task, and so far as she was able, she liked to plan her work ahead. Linn retreated with a careful tread up the stairs – in his sock feet, his boots were scuffed and dirty, very unlike their gleaming appearance he usually affected: only his hat escaped whatever misadventure that made him look … used. Linn came down the stairs, as silent as when he’d ascended: he’d come into the house still damp from washing up, and consultation with a mirror assured him that yes, he’d managed to get rid of the accumulated dirt: he looked around, remembering his young sons, alive and healthy (and clean!), and he gripped the back of a kitchen chair, then sat, slowly, bent over, elbows on his knees, and sank his face into his palms, shivering a little. The maid came bustling into the room, picked up his folded coat, shirt, vest and trousers, then froze, looking at the man: she placed the folded garments on another chair, slipped out of the room, came back with a cut-glass tumbler with three fingers’ worth of distilled California sunshine. “Ye look done in,” she whispered, a gentle hand on his back: Linn lifted his face from his hands, took the glass, drank. He handed the maid back the empty glass, nodded: another moment, and he was on his feet. “I’ve got t’ polish m’ boots,” he muttered, and the maid shrank back a little. Michael Moulton was the town’s attorney, and their land office agent: he’d lifted a chin to the Sheriff, crossed the street at a long-legged stride, spoken to the pale eyed lawman from whom silence cascaded like a cold downdraft from a snowy mountain. Linn looked at his old friend, concerned. “The Parsons boys?” Moulton nodded, a single, measured lowering of his head, a lift, eyes veiled as he did. “Those boys don’t have two shekels to rub together.” “So I gathered.” “And they were askin’ about filin’ a claim?” Again the single, measured nod. “Did they say what they were minin’?” “Not after I started talking how much filing a claim would run, then I spoke of the expense of hauling ore, the cost of freight …” “Hm.” Linn squinted into the distance. “Might ought I’d ride up there and take a look.” “Chances are it was just wishful thinking, Sheriff.” “Might be,” Linn agreed, “but if they hit even a trace of color, we could have a gold rush or silver or hell anything nowadays, mines are playin’ out left and right and men are desperate for one last vein.” The two men withdrew into the Sheriff’s office, and the Sheriff opened one of several wide, shallow drawers on a purpose built cabinet he’d had made some years back. He considered the contents of one drawer, riffled through the big sheets of paper, brought one out, laid it on his desk. Mr. Moulton turned to get his bearings, studying the hand drawn map – twin to the one he’d used that day, to locate the position of the Parsons boys’ inquiry – the Sheriff frowned a little, thumped the spot with a fingertip. “There’s nothing there,” he said finally, “no silver, no zinc, no lead, sure as hell no gold … why d’ they want to stake that?” “Salt it, maybe, sell it and make money?” “They don’t own the ground, they can’t sell it.” “Sell the claim, then.” “That,” Linn grunted. “Most likely that.” He shook his head. “Hell, if they’re goin’ to do that, they’ll bring a gold rush down on us and we’ll never recover!” Mr. Moulton had seen gold rushes and what they did to a town, and he agreed silently with the Sheriff’s sentiments. “I’ll head up there and see what they’ve got.” Half an hour later, the Sheriff’s stallion stamped restlessly as the pale eyed old lawman surveyed the scene. He frowned, leaned forward, squinted, willing himself to see more clearly – What’s that sticking out of that hole? Legs? One of the Parsons boys ran up to the hole, grabbed a leg, pulled: it was excavated into a sidehill, it looked like a collapse – The stallion surged powerfully forward, heading for the small scale but potentially deadly tunnel collapse at a mane-streaming, tail-floating, ears-laid-back, gallop. The maid looked at Linn, her expression serious. “Ye drank that like watter,” she observed. Linn looked at the tumbler, looked into its vacant depth, handed it to her. “Yep. Hole in it.” “Sheriff,” the maid said carefully, “be ye well?” Linn looked at her with a troubled expression, something she’d never seen before. “I was thinking of my sons,” he said, his voice most uncharacteristically faint. Linn seized the broke-handled shovel, attacked the cave-in like a personal enemy. He knew it would be bootless to seize the protruding leg and pull: too much of the boy’s body was trapped under the roof fall: he moved dirt fast, not in a panic but without any lethargy whatsoever, carefully avoiding trying to shovel such things as arms or other body parts. He seized the boy’s waist, hoisted, pulled: a shift, and he reset his feet, hauled up, pulled again: the dirt reluctantly released its grip, and the Sheriff brought the limp, unmoving figure from death’s grip, rolled him over. He’s not breathing. Linn looked around, frantic. How to get him to breathe! What did they use on the waterfront? Bent him over a barrel and rolled him back and forth … Linn remembered the near-drowning, how the dockworker was laid over a barrel, gripped by the ankles, rolled back and forth, how he’d heaved up a hogshead of saltwater and started coughing. I’ve got no barrel. He stood a-straddle of the boy, bent over, ran an arm under the lad’s belly, hoisted, then let him down: hoisted again, let him down again. The other boy’s pleas were distant, barely heard: the Sheriff felt helpless in the face of his tragedy, he felt uncertain. Lift again, hold, hold, hold, and lower. He felt movement: he lowered the lad again, rolled him up on his side, looked at the frightened brother, white-faced and kneeling, watching, shocked, wide-eyed, helpless. Linn reached down, rubbed the lad’s belly. He gasped, weakly. Linn rubbed again, harder. A longer gasp. Once more, he thought, and this time the boy coughed. Linn’s voice was quiet in the kitchen. “When he started breathin’ again,” he said, “so did I.” He took a long breath, stood. “Reckon I’ll get my boots taken care of,” he said quietly. “Got ‘em kind of dirty.” The maid rose with him, her hands clasped and anxious in her apron. “Did they find anythin’ where they dug?” she asked. Linn shook his head. “They found dirt, that was about all. Nothing they could claim.” “So we’ve no worry about a Glory Hole bringin’ scoundrels an’ loafers fra’ all o’er t’ plague our puir town.” “No.” Linn grinned. “I’ve seen a gold rush, Mary. No wish to see one here.” Mary withdrew a step to allow the man to pass, then: “Sheriff?” Linn stopped, turned. “Did ye talk t’ God about it?” Linn nodded, his expression haunted. “Yes, Mary,” he said quietly. “Yes, I did.”4 points

-

4 points

-

4 points

-

4 points

-

4 points

-

4 points

-

4 points

-

3 points

-

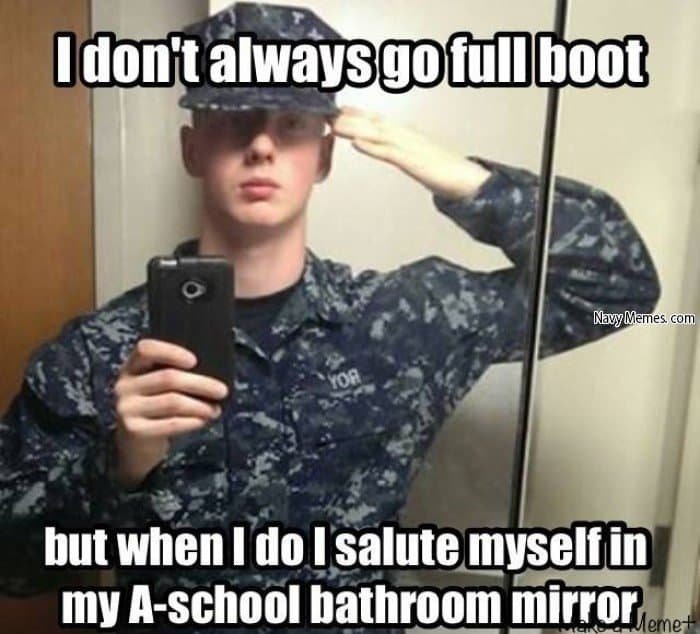

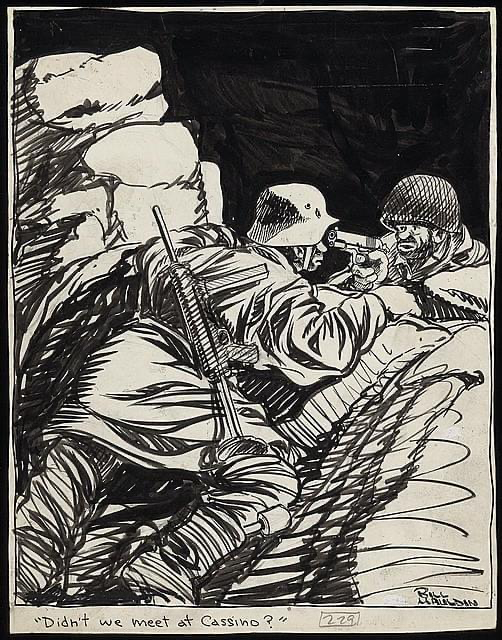

One just did. Tell us you were never in the Navy, without telling us you were never in the Navy. Kinda surprised me — I took over a division on the Forrestal, had to show my junior enlisted how to box their covers ‘old school.’3 points

-

3 points

-

3 points

-

3 points

-

3 points

-

3 points

-

3 points

-

3 points

-

3 points

-

I LIKE THINGS THAT WORK It used to be a winning poker hand. In less than one-half of one heartbeat, it was a fluttering spray of pasteboards -- that is, it was one of several such sprays. Colorful, light-catching, just like the glitter of coin launched into the air when an anonymous boot kicked the underside of the table and those nearest the sledgehammer concussion took pains to lose altitude in a hurry. A pale eyed deputy Sheriff, less than a week in town, tracked down a man who swore no man could track him; he'd braced him in the town he'd bragged no lawman would ever dare enter, and he'd just outdrawn the man who'd let it be known that no man alive could out-draw or out-shoot him. Later, after the inquest, the circuit riding judge asked the quiet, lean-faced lawman with the thousand-mile stare, "Deputy, why are you still carrying that old Colt? Surely you can afford one of those new cartridge revolvers!" Deputy Sheriff Linn Keller, the day before he became Sheriff of Firelands, looked the circuit riding Judge in the eye and said quietly, "Your Honor, that revolver was given me by a man who knew I would need a faithful friend who could argue loudly and persuasively on my behalf. It's never let me down, not even once." The Judge saw just a hint of humor in those pale eyes as the lawman continued, "I like things that work!" A pale eyed Marine was laagered in with her troops in mountains uncomfortably close to the Soviet Union: matter of fact, she'd found Soviet troops occupied this same bunker, years before. Her M4 carbine was detail stripped on the solid little table before her: she reassembled it, her fingers sure, swift, exact: she knew where dirt hid, where carbon built up, she knew which parts to look at closely, she knew what to change out and when. Nobody ever remembered her rifle failing to function, no one ever remembered her M4 out of action from a misfeed, from a jam, from a failure to eject. Nobody offered comment when they saw her tear her rifle down, but no one missed how precise she was when she did, and no one failed to notice that when this pale eyed Marine brought fire upon the enemy, the enemy came out in second place. The closest anyone ever came to comment was when her CO came in to find her carefully, precisely, exactly, lubricating and reassembling her rifle: he watched in silence, waited until her rifle was reassembled before lifting his eyes from her hands and looking at her eyes. Willamina's eyes were pale as she said in a quiet voice, "I like things that work." Three men moved at the same time, and so did a pretty young Ambassador in a long-skirted dress and a fashionably matching little hat. The men moved against the guard that surrounded the Ambassador, confident that surprise, strength, weighted leather saps -- and the energy-dissipation suits they wore -- would be sufficient to disable the guard and abduct this pretty slip of a high-value hostage. They moved, reaching for a guard's arm with one hand, raising their slungshot with the other. Ambassador Marnie Keller skipstepped to the side, fired a percussion, blackpowder, .36 caliber, Navy Colt: its twin, in her other hand, coughed: two men fell, the third, stunned by two quick concussions, looked at her just in time to see a pale eye, steady over the muzzle of her octagon barrel revolver. It was the last thing he ever saw. During the debrief that followed, Ambassador Marnie Keller helped strip the carcasses, showed the inquest the wire-mesh suits, the capacitors, the energy scavengers that would have soaked up all the energies of hand-held stunners her planet-assigned bodyguards carried. "They were ready for the defensive tools your troops were issued," Marnie said quietly. "They intended to cosh my guard, seize me and hold me for ransom and" -- she looked around, her pale eyes hardening as she did -- "and do terrible things to me to entice you to accede to their demands." She casually reloaded one revolver, then the other -- she slipped nitrated paper cartridges into the fired cylinders, turned the ram to seat the flat-nosed, conical bullets down on the powder: she capped the fired nipples, rested the nose of the color case hardened hammer on the little peg between the nipples: a quick move, a magician's gesture, the pistols were hidden again, and none there were sure quite how she'd done it, or where they'd gone. The Ambassador asked Marnie later why she hadn't worn her usual .357, if she'd known there would be an attack. Marnie smiled at him, demure, utterly charming, absolutely feminine as she said in a quiet voice, "I like the effect of fire squirting from the barrel. They'll never forget seeing that. "I like that blackpowder concussion, I like the smell of sulfur afterwards." Her smile was less feminine now as she added, "It lets 'em know their destination if they cross me." She folded her hands very properly in her lap and continued, "Besides, I like things that work!"2 points

-

2 points

-

2 points

-

2 points

-

2 points

-

2 points

-

I’m well acquainted with them. A skill scoffed at originally, but valued many years later when refinishing the floors of my house.2 points

-

There is a bunch of stuff I would cover in a basics class. With everything I see, the lack of a magazine in the well gives me absolutely no comfort.2 points

-

Don't worry Uncle Dave, I won't tell the ENTIRE WORLD that a picture of ham and pineapple pizza made you feel hungry; your secret is safe with me .... ......................... unless ...........2 points

-

2 points

-

2 points

-

2 points

-

2 points

-

2 points

-

2 points

-

Thank you. I was trying to make it some kind of joke about those confused people that don't know what they are. When I was a kid we call transmissions trannies.2 points

-

2 points

-

2 points

-

2 points

-

1 point

-

They would go shopping together, and occasionally go out to lunch. The 3 of us would go square dancing together. My ex and I also danced the rounds between tips. When I needed a break the two of them would dance the tip with my ex as the left hand (man's) part. My ex and her husband would on a somewhat regular basis would treat us to dinner out.1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

-

1 point

_02-781336.thumb.jpg.f4a75bbb74124e28370c8d589db5938f.jpg)