Leaderboard

Popular Content

Showing content with the highest reputation on 03/30/2024 in all areas

-

6 points

-

6 points

-

6 points

-

5 points

-

FENCE SETTIN' I wasn't sure at first. I thought it was my daughter Dana, settin' on the top rail of the whitewashed fence behind the barn, least until I got close enough to see her boots. I couldn't help but grin. Marnie wore red cowboy boots and Dana wore black, and these ... these were red. I clumb up on the fence and throwed my leg over, then my other leg and there I set beside my darlin' daughter, and her lookin' out over the pasture, her eyes full of memories. Dana and Marnie both braided their hair and wrapped it around their necks, and twice it spared them a throat-slash in a close encounter of the bladed kind: both times the attempt was not well received, and the individual that tried it, come out in second place -- one will be in prison another twenty three years, the other commenced to assume room temperature our friendly local coroner's slab. We set there side by side, neither of sayin' a word. I hadn't expected Marnie to show up. Ordinarily she'd open an Iris in my study and step out lookin' all gorgeous and ladylike in a McKenna gown, and she'd told me she was known in all the Confederate worlds by the way she dressed -- "brand recognition," she'd said, and smiled as she did. I waited for her to speak. If she was here, and she wasn't in her Ambassador's gown, she was here as just her, and that suited me fine. I saw her bottom jaw slide out and she looked down and said, "Daddy, do you remember when I first came out here?" "I remember," I said gently, for the evening was quiet, and there was no need to speak loudly a'tall. "You brought me out here to show me the horses." I thought of that evening, and how little she was ... four years old, no bigger'n a cake of soap, big eyed and scared of everything, even me. I didn't know quite what to do with her but I figured if I acted like I did, why, I might do something right, so we come out here behind the barn and I whistled up the mares and I let Marnie stand behind me as the mare come up and snuffed at my shirt front, and two others come up, and I unwrapped several of those red and white swirlie striped peppermints and proceeded to bribe the mares with 'em. I told Marnie horses bribe as well as any politician. She pretty much hid behind me, least until one of the colts come up, one of the little bitty fresh laid ones, I don't reckon he was more'n two days old: hungry, frisky, curious, he come up a-buttin' his Mama for a meal and she stood for it and Marnie watched that cold with big and solemn eyes and when he come up for air, why, Marnie started out from behint me just a little an' that colt saw her and I don't reckon either of 'em had ever seen a little bitty version of the full grown product before. I let nature take its course: Marnie was hesitant to touch the colt, but she did, and the colt laid his chin over her shoulder and Marnie looked at me with great big eyes and I said quietly, "He's giving you a horsie hug," and Marnie tentatively, carefully, gave the colt a hug. The mares wandered off and the colt followed his meal. I hunkered down beside Marnie and she looked at me with big and wondering eyes and she looked after the horses and I said "What are those called, Marnie?" and Marnie whispered "Horsie puppies." I couldn't help but grin to hear it. All this went just a-whistlin' through my mind in the two seconds after she asked if I remembered, and I allowed that I did. "I didn't know what a good man was," she said, her voice distant as she swam through memories of her own. She turned and looked at me and said "I never knew anyone could be gentle, but you were." I nodded slowly. "You taught me to be a lady, Daddy." Now that honestly surprised me, for I don't ever recall teachin' her how to sit or stand or walk with a book balanced atop her head, I never taught her to sew nor flirt nor pout, and Marnie laughed, for I reckon I looked surprised, or confused, or both. "You ... treated Mama like a lady. All the time. I don't ever remember your raising your voice, not once, not ever, inside the house." She smiled and interrupted me before I could say it -- "I know, Daddy, you dislike loud noises!" I laughed, nodded. My daughter knew me better than I realized, but I was not surprised at this. "I remember ... it wasn't much later, a week or so ... you asked me if I'd like to ride a horse." I nodded again. Marnie looked down, swallowed. "I was scared," she whispered, then she looked at me, and I could see that little girl she'd been, looking at me out of those pale eyes, alone, vulnerable, frightened. "I was scared to ride a horse, Daddy, I was scared to tell you no, I was scared to do anything that would raise your voice or raise your hand --" "You were walking on eggshells before you started school," I murmured. "Do you remember what you asked me next?" I smiled, for there was a memory I had chambered up and ready to go. Little four year old Marnie Keller wore a frilly dress, and knee socks and little saddle shoes, her hair was braided and she sat on the top rail of the fence behind the barn. The big man with pale eyes walked a spotty horsie up to her and it sidled up to her and he said, "You could ride with me. Come on over behind me, darlin'." Her pale eyes were uncertain, her face was pale, she swallowed hard, but she hooked her heel on the second rail down and leaned forward -- she grabbed the shoulder of his coat and she stepped over, onto the saddle skirt -- she had not the least idea that she could sit, and what Shelly saw when she came out to call them to supper, was a strutting Appaloosa stallion at an easy canter, mane and tail floating in the chilly evening air, a pale eyed man with a big grin on his face riding proudly in the saddle, and standing up behind him, a laughing little girl with even white teeth, a little girl with blanched-white knuckles as she death gripped the man's Carhartt shoulders, as she stood up behind him, feeling taller and faster and happier than she ever remembered being in all her young life! "I remember," I said quietly. "That was the first time you ever rode a horse. Your Mama still has the picture." I looked over at Marnie. "Do you know what I saw when I looked at that picture?" Marnie blinked, curious, smiled just a little, shook her head. "I used to stand up behind my Mama a-horseback, when I was that size. Mama had a picture, I don't know whatever come of it, but I remember ... feeling ..." I looked down and I couldn't help but smile. "Marnie, you looked happy. You looked at the world for the very first time with fearless eyes. When I saw that picture, I knew I'd done something right." Marnie reached over, laid her hand on mine. "You did many things right, Daddy. That's why I'm here." "Oh?" "I wanted to sit here and remember the first time things went right in my life." There are times in a man's life when he realizes just how profound an effect he's had, and this was one of those times. "I wanted to sit on the fence, Daddy. Here's where it all started."5 points

-

5 points

-

5 points

-

5 points

-

4 points

-

Smart ass...how else are ya suppose to see if the damn thing is working...wait till it pops out onto the floor?4 points

-

4 points

-

“BUGLER! SOUND RECALL!” A pale-eyed ambassador tilted her head and regarded the Judge: her expression, her posture, told His Honor that he had her undivided attention. She’d been formally received: on a world where the swiftest transportation was the fastest horse, the arrival of a boxy, chisel-nosed shuttle, shining and silent and descending from the skies, was unusual enough to catch the eye: the shuttle, as it always did for a State visit, descended along a prescribed course, and watchers knew to anticipate its approach from a particular direction, they expected to see it descend along a designated path: signals were passed, flashes of reflected sunlight if in the daytime, torches ignited in a particular pattern along relay-points, if at night. The shuttle’s course was long and straight; it came at a steady velocity, slowing only after crossing the river; one mile more, and it came to a stop, hovered, descended straight down in the middle of a grassy clearing. The pale-eyed Ambassador stood in the shuttle’s broad hatchway as the fan-shaped ramp lowered: a brass band greeted her with a brisk air, a distinguished representative removed his fine, tall hat and formally bade her welcome: only then did she set foot on the soil of this Confederate world. Ambassador Marnie Keller allowed the representative to take her hand, raise it to his lips: his expression was solemn, his eyes unusually so: Marnie knew the man to be a charming dinner companion and an expert dancer, and she also knew that his delight would be expressed with shining eyes and a cheerful voice. She saw instead a troubled man. A dignified woman in a McKenna gown sat across from His Honor the Judge. Tea was brought, hot, steaming, fragrant: Marnie had been instrumental in introducing both the Camellia shrub and Bergamot to the planet, and both were enthusiastically embraced: on this trip, she’d brought coffee plants, and complete instructions for their horticulturists, but for now, tea was a new drink, and very popular with those who could afford it. Marnie’s choice of the tea and bergamot was intentional. There were multiple well-established crops introduced to this world’s fertile soils. Marnie did love her Earl Grey tea, and tea had receded into distant legend in the common imagination. Her gift of plants the year before, with instructions on where to plant them, and how to care for them, when and how to harvest, was enthusiastically received. The first crops were carefully dried, brewed, sampled and pronounced good. Marnie knew that a very few containers of dried leaves were sold, among those few who could afford it just yet … and she knew these were sold in Japanned boxes with illustrations of a woman in a long gown, presumably her engraved image, pressed into the heavy paper boxes in four colors. “Your Honor,” Marnie said neutrally, “you have the look of a troubled man.” He nodded, set his delicate china teacup down, untasted. Marnie set hers down as well. If the matter was serious enough to warrant his emptying his hands and giving his full attention to what he was about to say, it was serious enough for Marnie to empty her hands and give him her undivided attention. “Are you familiar with our methods of execution?” he asked. “I am not.” “For particularly heinous crimes, we have the Pits.” “I am not familiar, Your Honor.” “I believe you have Coulter’s Hell on your world.” Marnie smiled, just a little, nodded. “I’m familiar with Coulter’s Hell,” she affirmed. “I have been through it several times.” “We have something similar.” “Is yours a place of execution?” “It has been. One pit is reserved for … truly terrible crimes.” Marnie waited as the man shifted uncomfortably in his seat. “There are mud pits in various colors. Our men of science tell me they can color up from mineral content, or from something they call algae.” “I am familiar with several varieties of colored algae.” “There’s one pit that has something in it. It’s not algae. If you throw … they tested it yesterday to make sure it works … they threw a dead chicken in it and watched it dissolve.” “Dissolve.” “We make condemned prisoners view this dissolution, one week to the day of their date of execution.” “And how are the prisoners executed?” The Judge swallowed, looked away, looked back. “Terrible things happened,” he said quietly, shaking his head. “Terrible. I hesitate to describe them.” “Your Honor, you’ll find I have a cast iron stomach. Please speak plainly.” “There was brutality, Madam Ambassador. Cruelty and monstrosity more terrible than a civilized mind can grasp. A man was found guilty, and he was placed in a small metal cage. The door was riveted shut and remains so.” Marnie’s eyebrow raised. “He was … his cage was placed on a wagon, and this was taken to the place of execution. “He was shown the ramp his cage would slide down and into this bubbling pit. “The dead chicken was thrown in and he watched as … as whatever devil’s soup lives there … dissolved the chicken.” “The prisoner will be dissolved alive.” “The pit is quite warm. I am told it’s not hot enough to boil a man to death, but he’ll scream with pain when he is introduced. The cage will sink to half its depth and he will … between the heat, and being eaten alive …” The judge shivered. “The family of his victim will be assembled, to witness this most horrible death.” Marnie nodded, tilted her head a little, studied the Judge’s face. “And you are quite sure you have the actual culprit.” The judge nodded, then shook his head. “There is always doubt, Madam Ambassador. Evidence was presented and the jury was convinced. This fellow … he is a known criminal, but to create horrors of the magnitude of which he is accused …” The Judge shook his head. “He was brought back from having been shown, and one week to the day from his guilty verdict, he will be slid down the ramp, still riveted in that small steel cage, and he’ll scream his last, while his victim’s family watches.” “And when will the execution take place?” “Today.” “Then I am just in time,” she murmured, and picked her tea up again. The Judge looked at his tea, still untouched, shook his head. Marnie placed her delicate teacup on its saucer just as an urgent knock drove against the inner chamber’s door: a messenger threw the door open, paper in hand. “Your Honor,” he said, “we convicted the wrong man!” The Judge powered to his feet. “Your Honor, when is the execution?” “He’s being taken there now!” “How do we stop it?” The Judge looked at the messenger. “Have my surrey hitched up!” “Yes, sir!” “Your Honor,” Marnie said crisply as they rose, “can we get to my ship? It’s swifter than –” “Yes,” the Judge said, “we can do that!” A bugler and a red-faced Sergeant rode ahead of the Judge’s surrey. The bugler blew a sharp summons, clearing the road ahead of them: the Judge’s face was grim, he had an arm clamped hard down against his chest, reins in his off hand. The chestnut was a pacer, and swift: she was a racer, and the lightweight, two-wheel surrey was a younger man’s carriage, but it suited the Judge, who remembered what it was to drive behind a fast horse, and never lost that love. Marnie spoke quietly into her lace-trimmed sleeve-cuff: as horsemen and a racing-style surrey came into the clearing, men came to attention on either side of the diplomatic shuttle: the boarding-ramp was down, the pilot was at the controls, Marnie hiked her skirts and jumped from the surrey, hit the ground running. Three steps and she was on the ramp, her hand gripping the Judge’s coat-sleeve. The ramp was only just beginning to whine shut when the shuttle jumped straight up like a scared jackrabbit, if a jackrabbit can make a hundred yards straight up in two seconds. “Does the condemned have any last words?” A known thief looked out through the bars that held him, crouched and cramped, for the past week. “Would it do any good?” he snapped. “I didn’t kill nobody, so be damned with you all!” The executioner nodded at an old man, who hitched a spring loaded hook onto a heavy ring welded to the back of the condemned man’s small cage: when the mechanism raised the back of the ramp and the cage slid into the pit, a team of mules would be used to pull the empty cage back up the timber ramp, as buckets of water sloshed the hungry mud off the metal, lest the mud it dragged back onto the wooden ramp, eat great gouges in the ramp. When the cage came out, they knew, it would be completely empty. The hungry mud would have eaten every particle of the prisoner. Silence descended over the scene: the executioner brought out his watch, consulted it. The prisoner, alone, naked, waited for the mechanism to activate, waited to hear gears and springs beneath him start to clatter, start to hoist the back of the ramp, start to slide him into Hell while he was still alive. Something silver streaked over the horizon toward them. The diplomatic shuttles were normally silent. This wasn’t. The shuttle screamed through the air, a high-pitched half-whistle, half-siren, louder as it approached, shining and arrow-swift, drawing a straight line for the Place of Execution. His Honor muttered, “If only we had a bugler!” “Bugler?” the pilot laughed. “We can handle that! What call, sir?” The Judge’s eyes widened. “Sound Recall!” The pilot’s hands danced over a small keypad, and Marnie smiled, just a little, as her uniformed Confederate pilot murmured, “Sound files, bugle calls, Recall.” Beneath them, a hatch opened, a bank of a half dozen loudspeakers dropped into the slipstream, adding to the ship’s rumbling vibration as it shrieked through the air. The executioner watched as the hand swept upward, biting chunks from a man’s lifespan with each tick of its mechanism. He gripped a short, smooth, cast-iron handle, waited for the appointed moment. The watch’s long, slender second hand touched the ornate, hand-painted 12 at the top of the age-yellowed watch dial. The executioner gripped a small handle, pulled, stepped back: the preacher began reading from the Book, and beneath the condemned man, beneath the riveted-shut cage, a powerful spring began to unwind, turning an axle, turning gears, turning a screw mechanism which hoist the back of the ramp. Heads rose, mouths opened as something boxy and silver stopped overhead, dropped straight down toward them, as the commanding, sharp, precise notes of Recall shivered the air. “STOP THE MECHANISM!” The executioner shoved at the short, cast-iron handle, shoved harder, desperately trying to stop what he’d started: he put both hands on the smooth, red-painted handle, shoved impotently at the locked bar, the well-greased mechanism sounding like it was chuckling at his efforts. The mule skinner spat a brown stream of tobacco juice, picked up the reins: “Yup there, now, yup, boys,” he called, and the mules surged forward, against the chain. The cage started to slide, stopped suddenly, held by the chain and by two mules. The shuttle landed, the ramp dropped, the Judge ran up, his hand driving into his coat. He pulled out his gavel. A Judge’s gavel was made of the hardest wood on the planet. Its handle was turned, shaped, given particular decorative looking rings that served as a key, as a signature: the Judge’s gavel was the only thing that could stop the ramp’s mechanism: as the silver diplomatic shuttle lifted, pirouetted, backed against the rising ramp, the landing ramp blocking the cage from sliding off smooth timbers, the Judge drove the handle of his gavel into the execution machine’s socket. Gears slammed to a stop. The Judge looked at the executioner. “We have the wrong man.” Sheriff Jacob Keller listened to his sister’s recounting of her latest diplomatic venture. “What happened after they got him out of the cage?” “They made the official proclamations that he was innocent, that the right man was found, the usual language.” “What about him? Any compensation for wrongful conviction?” “I argued that his reputation was stained beyond redemption and through no fault of his own. We agreed that a fresh start was indicated, so we moved him to another world entirely, someplace that had never heard of him or his homeworld.” Jacob raised an eyebrow. “I set him up with his own tea plantation,” Marnie smiled. “That was a year ago. Yesterday I received a package of tea by courier post, and a note.” She handed Jacob the note. I hope this blend is to your liking. It was signed with an ornate, capital R. Marnie raised a small, cloth-wrapped package, closed her eyes, took a deep, savoring breath. “He got the blend just right.”4 points

-

4 points

-

Rocks from cars either in front, overtaking you or coming in the other direction. You still see them occasionally, I suppose laminated front windscreens have made them more of a thing of the past and most insurance companies down here give you a replacement windscreen annually with your policy at no cost.4 points

-

4 points

-

4 points

-

4 points

-

3 points

-

3 points

-

3 points

-

3 points

-

3 points

-

3 points

-

DEDICATION: You’re about to hear a very private and personal true story involving one of the greatest entertainers in the world: John Denver. It shows that above and beyond John’s incredible celebrity, he was first and foremost a caring and loving man. This story is dedicated to all those who care, who “believe”, and whose hearts are cradled within the spirit of Christmas. At the story's end, I'll share a secret that no one knows. The Littlest Cowboy’s Christmas -Michael Chandler aka Kincade You remember one Christmas most of all. Maybe it was a gift you once received. Maybe a surprise visit from an old friend. You’ve enjoyed many, but this one was different. This one is mine. Many years ago, my wife and I lived on a small horse ranch in Little Woody Creek, just outside Aspen Colorado. My son Preston, now 42 years old with a family and two beautiful little girls of his own, was only about 3 or 4. My daughter Melissa, now 38, wasn’t yet born. During the winters, we’d hook up a snowplow to the front of our farm tractor. I’d bundle up Preston, plop him on my lap, and the two of us would chug up and down Little Woody pushing snow this way and that. Not because we had to. But because the two of us would feel so good on those freezing winter days, snuggled together, giggling, singing, and shoving snow around. We felt quietly important, tackling all those drifts, making paths, blazing trails, passing livestock with their flared nostrils throwing shafts of steam like medieval dragons, coming home to Jackie hours later with rosy cheeks and tall tales. During one early December, Little Woody Creek received several feet of fresh snow. Preston and I brewed up our hot cocoa, climbed onto our tractor’s steel seat and chugged up some untracked, snow-choked road. We didn’t know where it went. Only that it was waiting for us, and our tractor. At the end stood a snowbound home and an old green jeep parked outside. As our tractor pushed this way and that, and our laughter cut the crystallized air, a rugged-looking cowboy came out of the house. He walked up to us and asked, “Did somebody hire you to do this?” “Nope.” “Then why are you doing it?” he asked. “Cause its fun!” A wide smile crept onto the stranger’s face. He walked up to us both, stretched out his hand to shake mine. And so I did. I shook hands with one of the five best friends I’ve ever had in my life. “The name’s Joe” he said. “Joe Henry.” He had jet black hair and mustache, a chiseled face and well worn jeans topped off with a faded work shirt. He looked like he’d just come off a six week cattle drive. Not tired. Far from it. He looked alive and vibrant. And very rugged. Joe was a quiet sort. Never bragged. Very different. I would find out over the years that Joe is singularly driven to fulfill his own personal destiny, regardless of what others think of his reasons or motivations. A solitary man, nearly always alone, but never lonely. Preston and I asked what he was doing in this snowbound house. “Writing songs,” Joe said. “And books. And cowboy poetry.” Joe had been a miner and a boxer and a hockey player and a steamship sailor and a ditch digger and a real live buckaroo. We found out that his appaloosa stud Lefty was stabled in an old barn just up the road from our own home. Christmas was coming. And as it approached, Joe walked up to our house one day. He asked if Preston and I would like to come up to the barn Christmas Eve, and help him celebrate the season with his horse Lefty. Joe said he was making Lefty a Christmas carrot and oats pie, and that another friend was bringing his boy too. About Preston’s age. Said the other fella was a country boy, could play a guitar some, and that we could all sing a carol or two. So Christmas Eve arrived, and Preston and I went. The barn wasn’t more than a quarter mile from our house, so with a kiss from my wife, the two of us donned our winter coats, and walked up there in the moonlight, the frozen snow crunching beneath of soles of our boots. Joe greeted us the moment we reached the barn, sliding a stall door open so we could enter. It was a working barn. No concrete, no offices, no steel, no insulation, no electricity. Just sweet hay covering the dirt floor, a loft filled with the summer’s harvest, wooden pens and high ceilings crisscrossed by rough-sawn rafters. In the center, Joe arranged a half dozen hay bales on which to sit. Next to them stood a small evergreen tree. It had wax candles perched on its boughs, popcorn strings and a tin-foil star that Joe had made. One present rested beneath: Lefty’s Christmas carrot and oats pie. The fella with the guitar was there. He rose to greet Preston and me. His son stood at his side, no bigger than my own boy. He warmly introduced himself, but didn’t have to. I recognized him immediately. We all picked a hay bale and sat down. The candles flickered on the tree, throwing warm and darting shadows throughout the barn. Joe poured us each a cup of hot cocoa, and offered a plain Christmas cookie. Lefty peered from his stall, his shaggy head hanging over the gate, huge dark eyes watching us. I felt like the stallion knew why we were there, and what Christmas meant. As we toasted Lefty, as we toasted each other, the fella with the guitar began to play. We all sang Jingle Bells and Deck the Halls and Frosty the Snowman. We all laughed, we all hooted, we all forgot most of the second verses. Counting the livestock, less than six of us experienced something I had never felt before. True peace. Boundless joy. Utter humility. Friendship. And the meaning of Christmas. Finally, Joe got up and walked over to the tree, bending down to carefully pick up Lefty’s pie. As he turned and walked to the stall, the fella with the guitar began to softly hum Silent Night. Joe offered the pie to Lefty, and the horse began to eat. The barn was filled with only two sounds: Lefty’s slow and muffled crunch of those crisp carrots, and the guitar fella’s soft humming of Silent Night. I felt like I was in heaven. We all did. Lefty finished about the same time as the song, and we all stood there with glistening eyes and deep personal thoughts. We looked at each other, and Joe spoke. “Merry Christmas” was all he said. We all shook hands and said goodbye. Preston and I reopened the barn door, waved, and began our return walk home under a sky full of a trillion shining stars, each one brighter than the next. We didn’t say anything as we walked hand in tiny hand. We both know that what had happened was very special. Very important. Maybe even more than pushing snow around with our little tractor. When we got to the front door of our home, Preston looked up at me, tugging at my sleeve. “Who was the man with the guitar, Daddy?” Though known throughout the world by millions of people who adored him, his music, the Country Roads and Rocky Mountain Highs of his voice, it wasn’t important I mentioned his last name. “It’s John, Preston. The guitar fella’s name is John.” But that night, he and his young son were just another couple of cowboys, sharing Christmas Eve with a few friends, and an appaloosa horse named Lefty. Now, the secret: At the height of John's career, he would host Christmas specials on TV. You may have seen them yourself. At the end of each show, he would have the set decorated as an old barn. Hay bales, straw on the floor, a Christmas tree with a small round object at its base that no one could quite make out. John would sing to the children, and they to him. He would end the show in that scene, singing Silent Night. Though John never told anyone, he was reenacting that night in Little Woody Creek... a magical evening experienced many years ago this coming Saturday night, by 3 men, 2 little boys, and an appaloosa horse named Lefty. Merry Christmas from Josephine and Kincade3 points

-

3 points

-

3 points

-

3 points

-

3 points

-

3 points

-

Sanger A sandwich. Sanger is an alteration of the word sandwich. Sango appeared as a term for sandwich in the 1940s, but by the 1960s, sanger took over to describe this staple of Australian cuisine. Sangers come in all shapes and sizes for all occasions—there are gourmet sangers, steak sangers, veggie sangers, cucumber sangers, and even double banger sangers.3 points

-

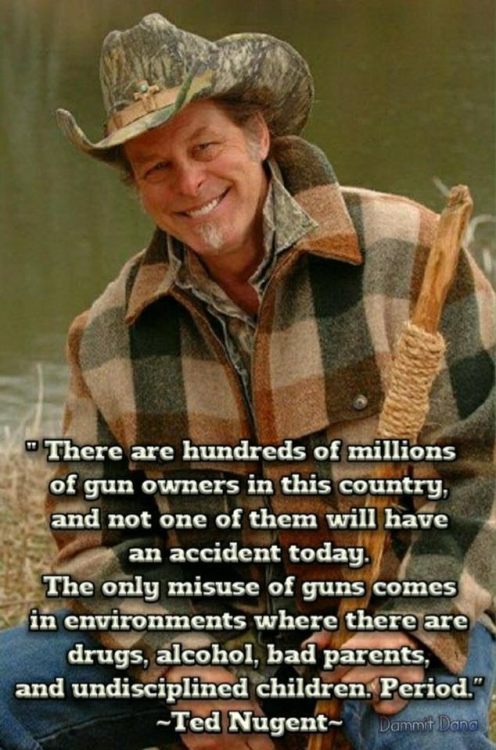

That's something that's puzzled me for years. Surveys on gun ownership. Let's suppose that my wife is very big on jewelry. And the guy from Gallup comes to the door and wants to know if I have any diamond necklaces. So I'm just going to tell him about the 17 diamond necklaces in my wife's jewelry box on the dresser? I don't think so. When any decent firearm is going to cost you at least $500, I can't see telling some stranger that yes you've got 17 guns. That isn't anybody's business. And then we have the "we are trying as hard as we can to make it illegal for normal people to have a gun" thing going on in DC, so I'm going to tell the Gallup guy that I've got all these guns? And then next year when they get outlawed, the feds are going to go to the Gallup people and subpoena their records? Find out who said they had all them guns, so they can go pick 'em up? I just don't understand why anybody would tell them.3 points

-

A few years ago both Pew Research and Gallup released survey results that estimated that about 43% of all households in the US had at least one firearm. Extrapolating from US Census numbers that means around 134,000,000 people have ready access to firearms. Also, about 40% of those households had at least one firearm that wasn't in a safe or other secured place. This, in my opinion, shows how rare accidental/negligent shootings are, and what a tiny portion of 1% of gun owners, much less the overall population, misuse firearms in the commission of crimes.3 points

-

3 points

-

3 points

-

ARE YOU AN ANGEL? “Grampa?” An old man snorted and blew as he scrubbed his face with a double handful of good cold freshly pumped wellwater. A little boy cocked his head and regarded his ol’ Granddad curiously. The old man, as was his habit, was stripped to the waist before he washed up: like most men of his vintage, he was lean, his skeleton could be seen – most of it, at least – the result of a hard life and hard work and many years. He reached up, pulled down a flour sack towel, rubbed wet arms and his wet face, briskly scrubbing water from his ancient hide, looked at his grandson. “Eh?” “Grampa, how come your ribs is funny?” the boy asked, pointing. “Hah? Them?” The old man approached his grandson, sat down on a handy sawed chunk. “You mean here?” The little boy traced careful fingertips down the irregularities, nodded, his eyes wide and solemn. “Does it hurt, Grampa?” “Sure as thunder did,” the old man grunted. “What happened?” The old man snorted, coughed, laughed and coughed again, spat. “I was young oncet,” he said. “Warn’t that long ago, neither. Hold old are you, boy?” “I’m five, Grampa.” “I used to be five,” the old man said thoughtfully. “Built me a cabin, too.” “You built a cabin when you were five?” “Oh, ya. I was about your size too.” “Grampa,” the lad said skeptically, “ya did not!” The old man frowned, hawked, spat, rubbed his stubbled chin. “Well, hell, maybe I was a little older,” he said, “but I near to kilt myself buildin’ it!” He’d laid out how he wanted to notch the logs, and notch them he did. He’d cut them to a uniform length. John Noble was a young man and John Noble was an exacting man, and John Noble knew whoever looked at what he built, would judge him by the skill of his work, and he, John Noble, was not about to do anything but first rate work! He’d sawed his logs to a uniform length. He’d laid stone for the foundation, rather than lay logs directly on dirt: most cabins were quick and dirty in their construction, built in a hurry to beat the cold weather: John laid out where he wanted the cabin set, he leveled the ground, what little had to be leveled off, he set his stones where he wanted them. He was better than a fair hand with an adz, and God be praised he had one: he’d made trade for tools, he’d found or scrounged or bought others: he drilled holes, cut pegs, tapped in the wooden stays that would hold his logs tight. John worked as young men work – steadily, mightily, putting the lean cords of muscle and sinew against the weight of fragrant timber. He’d cut skids and he’d used his mule and good hemp rope to skid timbers, cut flat on the bottom and on the top, he’d set them tight atop one another, he eased one heavy timber after another up the skids and to the top of the walls he was raising. He was doing well for one man working alone, until one of the skids kicked out and the timber came down on top of him. Sheriff Linn Keller knew there was a cabin being built, and he knew roughly where, and frankly he was curious to take a look at it. When he came in sight of the cabin, his stallion surged forward into a gallop. “There I was, a-layin’ under attair log,” his Granddad said in his old man’s voice, “and damned if this-yere fella didn’t come just a-gallopin’ up on an honest to God Appaloosa stallion.” “A stallion?” his grandson asked in a awe-struck voice. “Damn right, a stallion,” his Granddad nodded. “Know how t’ tell an honest to God Appaloosa stallion?” His grandson shook his curly-haired head. The old man raised a clawed hand up in front of his mouth, two fingers extended, curled a little. “They got fangs, they do, an’ they eat bears an’ bull elks f’r breakfast!” The old man winked and the boy grinned uncertainly – his Granddad didn’t always tell things the way they really were, but he was his Granddad and he was old and that meant he was really smart and maybe stallions really did eat bears an’ bull elks! “Anyway when attair log come down atop of me, why, one end hit a rock ‘r it would’ve mashed me flat an’ kilt me t’ boot!” “Grampa,” the boy said softly, “I’m awful glad it didn’t!” The old man leaned closer, screwed one eye shut: “Me too, sonny, me too!” Linn set a chunk on the rock the high end of the log was resting on. He tucked his backside, gripped the timber, took a long breath, took another, gritted his teeth. He brought the log up and over and on top of the chunk he’d just set there. It seemed steady enough – Linn grabbed another chunk, set in beside it – he went around, ran his arms under the injured man, pulled him out from under. Linn knew he hurt the man, pulling him like that, but he knew he had to get him out, get the timber off him. He didn’t know what else to do for the man. “Oh it hurt, all right,” the old man said thoughtfully. “It hurt like two hells and a sledgehammer, but y’know what?” “What, Grampa?” the boy breathed. “I’m alive t’ complain about it. Y’know why?” “Why, Grampa?” The old man leaned closer again, looked very directly at his grandson, his expression suddenly, humorlessly, stonefaced, serious. “There’s angels in this world, boy,” he said, “an’ one of ‘em rode that Appaloosa stallion.” “Really?” the boy asked in a marveling voice. The old man nodded. “You c’n tell,” he said, “there’s white about an angel, boy, and this one … when I looked up I seen them white eyes an’ that’s how I knew.” He nodded again, his own eyes growing distant, seeing the memory again. “I likely passed out, must’ve. Come to an’ there was folks tendin’ me. Found out ‘twas an honest t’ God surgeon workin’ on me. His boy’s the doc over’n Firelands.” “Dad?” a woman’s voice called. “Coming?” The old man sighed, stood, hung the flour sack towel back on its peg. “Help me back int’ m’ Union suit, sonny, yer Mama wants t’ eat.” A new student, a new school year, and Miz Sarah was greeting each one personally, as she always did. One little boy, shy the way new students often are, had trouble raising his eyes from the floor. When he did, when Miz Saran bent over and asked gently, “And what is your name?” he looked at her – his eyes grew big, startled, his mouth opened into an absolutely surprised O – “My name is Sarah,” she said. “Do I know you?” He swallowed, blinked, looked left, looked right, blinked again, and then he whispered, “Are you an angel?” Miz Sarah smiled, just a little: she went down on her knees, rested her hands gently on his young shoulders, drew him closer, laid her cheek against his and whispered, so only he could hear: “Nobody else knows,” she said, her sibilants tickling the fine hairs on his pink-scrubbed young ear: she drew back, smiled gently. “Our secret?” A big-eyed little boy nodded, awe struck. In his young mind, a promise was a promise. An angel asked him to keep their secret. When he was a little boy, his Granddad told him about seeing an angel, and how to recognize one. When he became a Granddad, he told his young grandson about his Granddad, and how he’d seen an angel, and he told his young grandson about the angel he met when he first started school. A little boy came home from school, his eyes shining with excitement. His mother recognized the signs, and smiled quietly as she set a saucer in front of him with his usual after-school peanut-butter-and-jelly sandwich. He usually devoured his snack, then ran outside to play: she watched him eat slowly, thoughtfully, completely at odds with the contained excitement in his eyes. His Mama sat down, tilted her head a little, studied her son. “Did something happen today?” she asked quietly. He nodded. “Can you tell me about it?” He blinked rapidly, nodded. “Mama, they sent an angel to Mars today!” he whispered, his eyes big and sincere. “An angel?” she asked. He nodded. “She looks just like us, Mama, but Grampa told me what to look for!” Later that night, on the evening news, the split-screen portraits of Marnie Keller and Dr. John Greenlees Jr were shown: the local station was making much of the local folk chosen for this second Martian launch, the big colony ship that would absolutely establish a long-term human presence on another planet. “There she is, Mama! Do you see it?” “See what, Bobby?” He pointed, his voice as excited as his expression: “Grampa told me what to look for! Right there, Mama! See it?” His Mama looked at the TV screen, and the formal portrait of the pale-eyed Deputy Sheriff Marnie Keller looked back at her. “She’s an angel,” a little boy’s voice breathed.3 points

-

2 points

-

2 points

-

2 points

-

2 points

-

2 points

-

No one thinks about baseball? I'm not even a sports fan, but that's the first thing I think of when I hear "homer". A four bagger. The second thing is D'oh.2 points

-

2 points

-

2 points

-

2 points

-

2 points

-

2 points

-

2 points

-

2 points

-

And howdy back, Thanks for trying and sharing. I have no idea how to post a video here in the saloon. If you were gunfighter... which you are... I'd be in the dirt, dippin' gumbo. At the time, I remember how cold the barn was that Christmas eve. We could all see each other's breath, especially Lefty the appaloosa. Joe Henry, one of John's most prolific song writers... the "Joe" in the story... still lives in Little Woody Creek outside of Aspen. Joe's name is on many of John's songs. Just check your albums. Joe has a wonderful cowboy book called "Lime Creek." Fantastic short tales, linked one by one. One of Joe's stories in Lime Creek has to do with that Christmas eve with John in the barn. But the names are different. Joe, however, has never changed. Only the color of his hair... just like the rest of us. If you'd like to take a peek at Joe's book, click on this link: https://www.amazon.com/Lime-Creek-Fiction-Joe-Henry/dp/1400069416/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1482464413&sr=1-1&keywords=Lime+Creek%2C+Joe+Henry1 point

-

Thanks Yul. I first shared this story with friends a long time ago. Others then heard it. The story became especially popular in Aspen folklore. Then, after telling the story to one of the stunt gunfighters I worked with at the National Western Stockshow in Denver, he offered to illustrate the story for a Christmas book. I had no idea he was an accomplished artist. All I knew was that he shot me a lot in the shows. So, over a period of two years, this man... Terry Jacobsen... painted amazing color pictures of that night. Once done, Pelican Publishing released "The Littlest Cowboy's Christmas". That book is a Christmas best-seller. And beautifully illustrated. Parents and grandparents love reading the story to their little ones Christmas eve. John Denver has a CD in the book that has him singing "Silent Night", just as he did in the barn that night so long ago. If you'd like to see the cover of the book and see part of Terry's work, click on this link: https://www.amazon.com/Littlest-Cowboys-Christmas-Music-CD/dp/1589803817/ref=asap_bc?ie=UTF8 Kincade1 point