-

Posts

8,747 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

73

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Everything posted by Buckshot Bear

-

I like federal primers and don't mind the big packaging but really dislike those aggravating tabs.

-

-

Finally, I thought I would try an eggplant

Buckshot Bear replied to Father Kit Cool Gun Garth's topic in SASS Wire Saloon

What a way to ruin good Vegemite!!!!!!!!!!!!! -

That was a great movie, watched it again not all that long ago.

-

-

A Queenslander is drinking in a West Australian Pub when he gets a call on his mobile phone and as he listens to the call he starts grinning from ear to ear, then when he disconnects he shouts to the barman that he wants to buy everyone in the bar a drink. The barman starts serving the drinks and the people start to crowd around keen to know what they are celebrating. "Well," he announces, "My wife's just produced a typical Queensland baby boy weighing 25 pounds". Nobody can believe that any baby can weigh in at 25 pounds, but the Queenslander just shrugs, "That's about average in Queensland . Like I said, my boy is a typical Queensland boy." Congratulations showered him from all around and many exclamations of "STREWTH" and "BLOODY HELL!" were heard. One woman even fainted due to sympathy pains. Two weeks later the Queenslander returns to the same bar. The barman says "You're the father of that typical Queensland baby that weighed 25 pounds at birth aren't you? Everybody's been having bets about how big he'd be in 2 weeks, we were going to call you. So - how much does he weigh now?" The proud father answers: "17 pounds." The bartender is puzzled and concerned. "What happened? He weighed 25 pounds the day he was born!" The Queensland father takes a long s-l-o-w swig from his XXXX Gold beer, wipes his lips on his shirt sleeve, leans onto the bar and proudly says, "We had him circumcised!"

-

You don't appreciate a lot of stuff in school until you get older. Little things like being spanked every day by a middle-aged woman. Stuff you pay good money for later in life. Bob Hope

-

Never knew this was a Pommie, thing.....always thought us Aussie's had come up with it https://www.smh.com.au/traveller/inspiration/in-praise-of-britain-s-greatest-culinary-invention-the-chip-butty-20240123-p5ezhg.html

-

Take me take me take me take me take me take me take me take me take me take me take me!!!!!

-

-

-

-

Australia must consider bringing back conscription as ‘all-out war’ with Russia looms https://www.news.com.au/technology/innovation/military/australia-must-consider-bringing-back-conscription-as-allout-war-with-russia-looms-expert-says/news-story/b1ced960b821027163b05b15ad47e5e6 There must be things behind the scenes happening for even hinting at bringing back subscription, seems the world is a powder keg. I'm sure that the U.S is going to have to hit Iran hard after the deaths yesterday of U.S serviceman. The fact the Australia is getting Nuclear subs from the U.S (Australian Navy personal are already in the U.S training on nuke subs) and is just the third nation after the U.S & U.K to have secured a stockpile of Tomahawk Cruise Missiles from the U.S, our increasing number of RAAF F-35a fighters and the increasing number U.S bases in North Australia.......the think tanks must be considering that something is imminent.

-

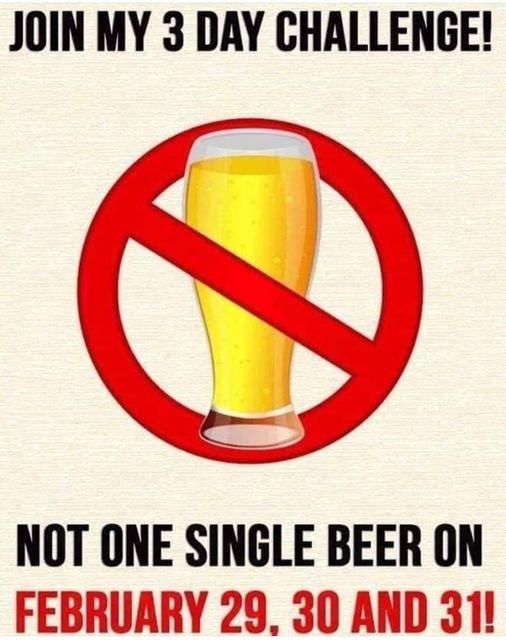

I'll have to plan ahead and get suitably plastered on the 28th enough to sleep right through the 29th. Damn leap year!!!!

-

They've got a bit of holster wear now in three years Eyesa and to me they look even better now mate.

-

-

-

-

-

A 27-year-old engineer/farmer from Freeling, a small town in South Australia, about 60 km north of Adelaide, it neighbours the Barossa Valley wine region, has paid tribute to his country ahead of Australia Day with an incredible art piece carved into his family’s paddock

-

(16).jpeg.f62eb3710929ae307c9cd0b09c217098.jpeg)