-

Posts

6,104 -

Joined

-

Last visited

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Events

Posts posted by Charlie MacNeil, SASS #48580

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

3

3

-

2

2

-

3

3

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

And that, loyal readers, is the original story of the town and people of Firelands as told by a variety of folks over a long space of time both modern and old. I hope that you have enjoyed our small efforts in presenting a town and a group of people who have been, and continue to be, near and dear to our hearts. Thanks for sharing your time with us.

-

1

1

-

-

Linn Keller 1-25-14

The Sheriff's son waited patiently as his father's pen moved methodically across good rag paper.

A newspaper, folded and forgotten, lay on a chair against the front wall; bold headlines screamed of war, the date was 1914, but neither man had any care for the state of the world.

The ache each man felt was too fresh.

Final entries had to be made before the book was closed, he knew; work was yet to be done, the young deputy knew, and he was standing ready to do the work, but he ached ... a deep, a bone-deep ache, far worse than any physical exertion.

The Sheriff's face was wooden as he wrote the final lines and let them dry, then he stood and closed the book, gently, almost reverently: his finger tips caressed the book's cover, then he took a black silk ribbon, wrapped around it longways, then crossways, tied it in a slip knot at the precise middle of the front cover: he opened the top right hand drawer and put it precisely where it always went, wiped the pen's leaf-shaped nib and set it away, then the bottle of good India ink, and closed the drawer easily, gently ...

He closed the drawer with respect.

Sheriff Jacob Keller looked at his tall, slender son, waiting at his side, his eyes quiet, tired-looking as a young man's eyes will be when the young man is in grief and trying to bear up under its crushing weight.

Like his father, Joseph would grieve in his own way, and at his own time: for now, there was work to be done, and like his father, and his grandfather before him, he shoved his feelings down into a long-neck bottle and stoved the cork down hard after it.

It took them some time to empty the Sheriff's office of its contents.

The tornado and the fire had damaged much of the structure's outside; the contents were mostly undamaged, and Jacob intended they should remain so.

He and Joseph knew of a mineshaft that underlay the town, a branch of the same shaft that collapsed under the boarding house some time ago: that branch was sealed off, but this one remained, and it was dry.

It took them some labor but they got the Sheriff's desk and office chair, their contents, even the pot belly stove, packed into that mineshaft: they'd brought in sheets of lead and some tools, they carefully crated, then sheathed, these memorabilia of his father's administration here, underground, safe in an inert, sealed container: his revolvers, his rifle, even his double gun: both Jacob and Joseph held Linn's ivory-handled Colts, one last time, remembering the man who'd worn them.

Father and son each pretended not to notice the other's face was wet.

Before they closed up the wooden crate, Jacob opened the bottom right hand desk drawer one last time, withdrew two heavy bottom glasses and the bottle of whiskey, handed them to Joseph; only then did the pair crate up and seal the desk, they set these last tokens aside, and they finished their task in silence: finally they withdrew from this dead end, carrying their tools and the bottle and the glasses, and at the first bend, they began work again, erecting a wooden wall, here where the ceiling was low enough they had to duck a little: they built it stout and wedged the corners tight, and by the light of their two kerosene lanterns, Jacob painted "DEAD END" and under that, "PLAYED OUT" -- the common means used in that mine to let future miners know that the gold strata ran elsewhere.

They were more than a mile underground; it took them a bit to walk out, and when they neared the mouth of the mine, Joseph asked, "Pa, what of the office?"

"I have another desk," Jacob replied, "and a chair. What's left we'll tear down and rebuild, but I want to rebuild in stone."

They stopped and looked around before emerging into daylight; they puffed out the flames, set the lanterns where they'd found them, in a little niche, whistled to their mounts.

Joseph hesitated before mounting, running gloved fingers over his gelding's brand. He rode a good looking Macneil cross, a short-coupled, tough-as-nails cross between an Appaloosa and a Mexican-blooded copper mare that hated men and outran anything this side of the Rio.

"I miss him, sir," Joseph said, his voice thickening.

Jacob nodded.

The two rode back into town, father and son, Sheriff and deputy: they rode in silence together, listening to the wind, to the distant scream of the ore train's whistle, they rode around town and in behind it and finally they made their way into the town's graveyard, and around a curving little roadway, and stopped at the raw earth of a fresh grave.

They dismounted, ground-reined their mounts.

The stone was broad and heavy and said KELLER in bold letters.

On one side, a carved triplet of roses, and over these, ESTHER, and in more delicate characters, "Beloved Wife."

On the other side, a Masonic arc-and-compasses, and the name LINN, and under that, "Beloved Husband."

There were fresh roses, four on each grave; the Sheriff and his son knew that Sarah and the girls had been there earlier that day.

Jacob uncorked the whiskey bottle.

Joseph held out two glasses.

Water-clear gurgled into the heavy-glass tumblers, two fingers' worth: Jacob turned and said in a loud voice, "Sir, we'd be pleased if you'd take a touch with us," and he poured a generous gurgle onto his father's grave.

The two men tilted up their glasses and drank.

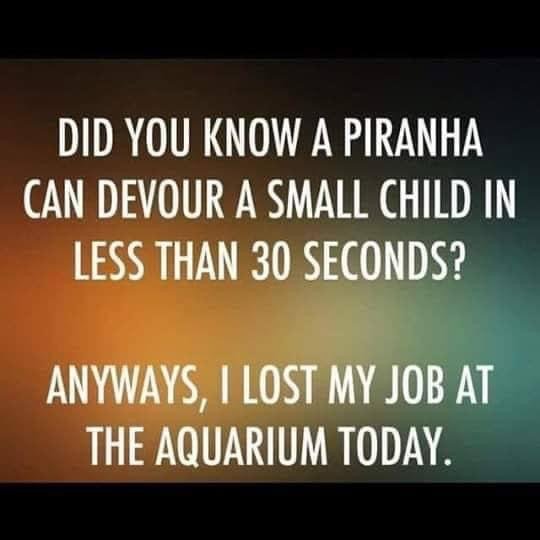

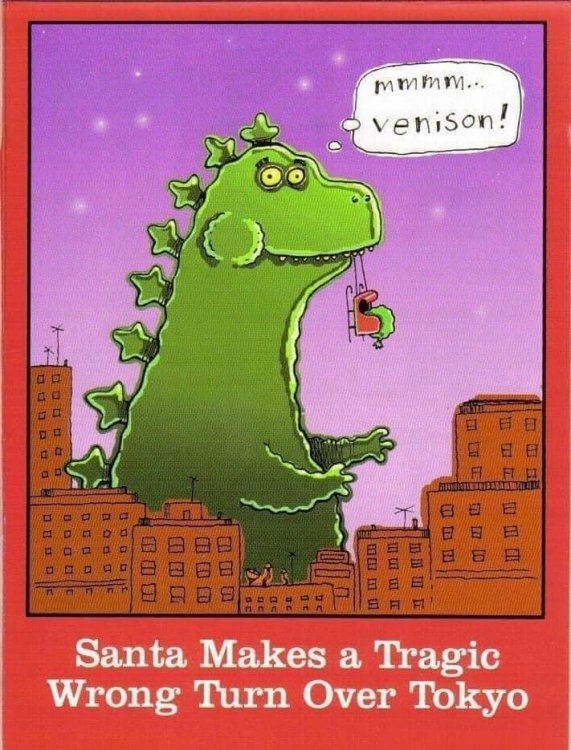

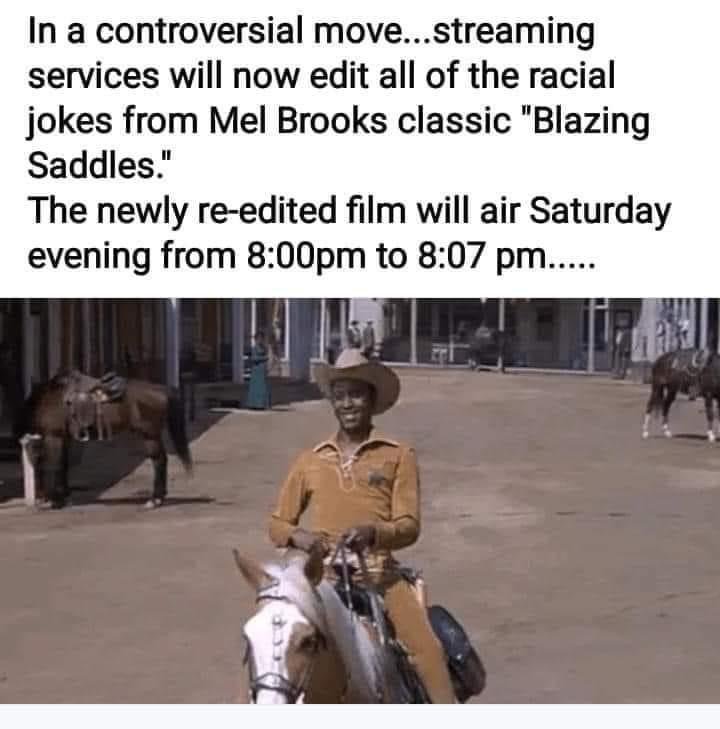

Ba-Dump Tissssh - Memes

in SASS Wire Saloon

Posted